A team of researchers, including a Johns Hopkins University evolutionary biologist, has made a significant discovery regarding an extinct giant meat-eating bird known as a terror bird. Their findings, published on November 4 in Palaeontology, suggest that this bird may represent the largest known member of its kind, offering new insights into the fauna of northern South America millions of years ago.

Discovery of the Fossil

The research focuses on a leg bone of the terror bird found in the Tatacoa Desert of Colombia, which is considered the northernmost evidence of this species in South America. The study was led by Federico J. Degrange, a specialist in terror birds, and included contributions from Siobhán Cooke, Ph.D., an associate professor of functional anatomy and evolution at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

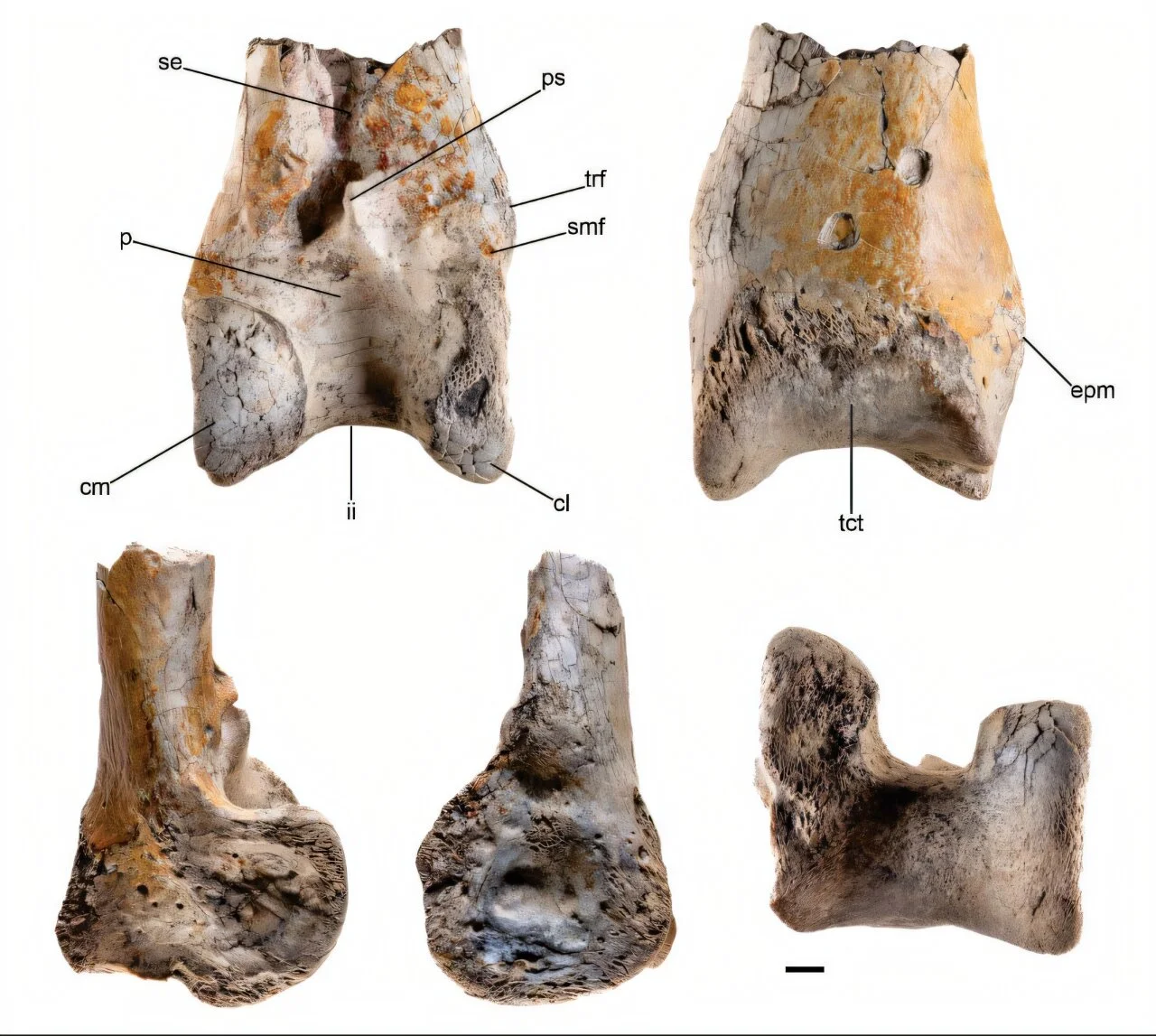

The bone, specifically the end of a left tibiotarsus (akin to a human tibia), suggests that this terror bird was approximately 5% to 20% larger than previously known phorusrhacids, with known terror bird species ranging from 3 to 9 feet in height.

Characteristics of Terror Birds

“Terror birds were ground-dwelling creatures, adapted for running, and primarily preyed on other animals,” Cooke explains. The fossil’s unique features, including deep pits characteristic of phorusrhacids, were complemented by evidence of predatory interactions, as it bore probable teeth marks from an extinct caiman species, Purussaurus, which could grow up to 30 feet long.

Cooke posits that the terror bird likely died from injuries sustained in an encounter with these formidable crocodilians, which roamed the region 12 million years ago during the Miocene epoch.

Implications of the Finding

Traditionally, most terror bird fossils have been located in southern South America, particularly Argentina and Uruguay. The discovery of a phorusrhacid fossil in northern Colombia indicates that these birds played a significant role in the predatory ecosystem of the region. The findings also provide a clearer picture of the biodiversity present in what is now a desert landscape but was once characterized by meandering rivers teeming with life.

During the Miocene, this area would have been home to a diverse array of animals, including primates, hoofed mammals, giant ground sloths, and large glyptodonts (armadillo relatives the size of cars). Today, the modern-day seriema, a three-foot-tall bird native to South America, is considered a relative of the phorusrhacids.

Ecological Context and Future Research

The research illustrates a distinct ecosystem that differs from both contemporary and historically known environments. Cooke remarks that this finding highlights how the terror bird species might have been relatively rare among the region’s other wildlife 12 million years ago.

The study raises the possibility that additional fossil specimens in existing collections may yet go unrecognized as terror birds due to the less distinctive nature of their bones compared to the leg bone analyzed in this study.

Cooke reflects on the significance of the discovery, noting, “It would have been a fascinating place to walk around and see all of these now extinct animals.” The collaborative effort of researchers from various institutions further enhances our understanding of the past, shedding light on the complex ecosystems that once existed in ancient South America.