Typically, monkeys and dogs took the cosmic test for human space survival. But 60 years ago, the French scripted an extraordinary chapter with a surprising twist

In just a few weeks, the space community will celebrate an exceptional milestone: the 60th anniversary of an unprecedented venture—the launch of the very first cat into space.

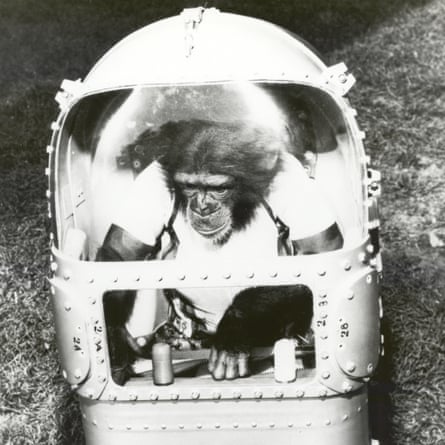

Félicette, a petite black-and-white stray from Paris, etched her name into history in October 1963. Aboard a French rocket, she embarked on a sub-orbital mission that soared to a remarkable altitude of 154km, charting a course where no feline had ventured before or since.

Amidst an era where dogs and monkeys were the preferred candidates for assessing the perils of space and the viability of human space travel, France embraced an unconventional approach. Fourteen stray cats, nameless to deter undue attachment, were curated by the team at France’s Cerma (Centre d’Enseignement et de Recherches de Médecine Aéronautique) to select a feline pioneer. C341 emerged as the chosen candidate.

Following the announcement of C341’s flight aboard the Veronique rocket on October 18, 1963, and her safe return, the French press felt compelled to honor this celestial trailblazer. Initially tagged Felix, the chosen name for the adventurous feline, a delightful twist surfaced—C341 was actually female. Thus, Félicette became her befitting appellation, commemorating her extraordinary odyssey beyond Earth’s bounds.

By enlisting Félicette for a cosmic voyage, France expanded the roster of spacefaring creatures—a lineage that has welcomed an assortment of surprising animal astronauts over the years.

The tradition of launching animals into space traces back to the late 1940s when US scientists chose an unlikely pioneer for celestial exploration: fruit flies.

A cohort of Drosophila melanogaster hitched a ride aboard a V-2 rocket, repurposed from Nazi Germany’s arsenal, soaring to 109km. Upon its return to New Mexico, scientists scrutinized the effects of cosmic radiation on these resilient flies.

In subsequent US missions, monkeys were propelled beyond Earth’s confines, their crafts returning amid tragic accounts of suffocation or parachute failures.

Yet, it was the Soviet canine, Laika, plucked from Moscow’s streets, who etched an indelible mark as an iconic space traveler. Aboard Sputnik 2 on November 3, 1957, she became part of history, riding within only the second satellite to orbit Earth, captivating the world with her pioneering journey into the unknown.

At the time, most media coverage of her journey focused on its implications for the US-Soviet space race and the cold war. Nevertheless, there was criticism of the mission, with the UK National Canine Defence League calling on all dog owners to observe a minute’s silence on each day that Laika remained in space.

Later missions were designed to bring animals safely back to Earth after their flights. Some were successful, some not. In July 1960, dogs Lisichka and Bars died when their Soviet launcher exploded shortly after lift-off.

However, this mission was followed by the successful launch and safe retrieval of a capsule carrying dogs Belka and Strelka later that year. According to Animals in Space by Colin Burgess and Chris Dubbs, the Soviet Union launched dogs on rockets 71 times between 1951 and 1966.

Today, rules governing the use of animals in space experiments are much stricter, added Foster. “Animals are also being put into orbit for different reasons. Modern missions are less concerned about testing the dangers of space and focus more on researching the long-term effects of living in space. That, in turn, reflects an interest in developing long-term missions such as trips to Mars.”

In addition, scientists study various lifeforms in orbit – mainly on the International Space Station – to unravel the influence that gravity has on living organisms on Earth. In orbit, gravity’s pull is very much lighter than on Earth, and this can shed light on how the growth of animals and plants proceeds.

“Plants develop differently in microgravity,” said Nasa scientist Jennifer Buchli. “They don’t know which way is down any more. They no longer have a gravity signal for their root structure. So we examine their RNA to see how it’s giving directions and signals, and how that differs from the way plants behave on Earth.”

Another ISS project, highlighted by Foster, involved mice that spent 90 days there as part of a study to see how sleep schedules and guts respond to being in space for so long. “They had mice up in space and a control group on Earth to compare results.”

Perhaps the most astonishing act of space survival was demonstrated by the water bear, or tardigrade, a microscopic invertebrate that can tolerate the hottest and coldest environments on Earth, and can survive decades without water.

In an intriguingly titled experiment called Tardis (Tardigrades in Space), a European research team sent 3,000 of these little creatures into orbit, where they spent 12 days on the outside of a rocket. Remarkably, 68% of them survived the cold, zero gravity, vacuum and radiation. “The water bears are something new. Nobody knew about that capability,” said René Demets, a European Space Agency project biologist.

The notion of space travel as a fatal journey has shifted, with scientists asserting its safety. Unfortunately, Félicette’s fate didn’t align with this optimistic outlook. Despite surviving her space flight and return to Earth, her capsule landed askew, leaving her dangling upside down—a peculiar and distressing sight until she was recovered.

Tragically, Félicette faced an even grimmer destiny. Two months post-flight, she was euthanized for scientists to scrutinize her body for potential anatomical or physiological impacts. Regrettably, the autopsy yielded no valuable insights. This marked the end of sending cats into space, and France abandoned aspirations for its own astronauts.

Nevertheless, Félicette’s legacy endures. In 2019, a statue immortalizing her was unveiled at the International Space University in Strasbourg. Poignantly seated atop a globe, gazing upward, she remains a symbol of valor and curiosity, commemorating her extraordinary journey beyond Earth’s bounds.