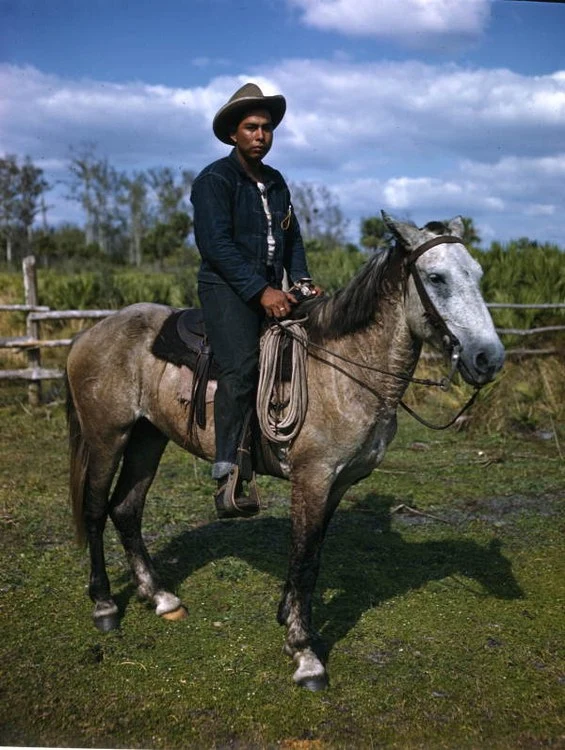

Long before the open ranges of the American West, the first true ranchers in North America were Native Floridians — the Seminole people. Today, their descendants continue that legacy, raising world-class cattle and earning top dollar for their herds.

This decade marks 500 years since the origins of Native American ranching, which began when a small group of Indigenous Floridians captured 20 head of cattle from the landing party of Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de León in 1521. The Spanish sought to colonize Florida, but fierce resistance from the native Calusa forced them to retreat. In their wake, they left behind the animals that would spark a centuries-old ranching tradition.

From the Calusa to the Seminoles: A Legacy Takes Root

The Calusa quickly took to raising the Andalusian cattle, finding that the animals thrived in Florida’s warm, grassy environment. “It was just great cattle country,” said Seminole rancher Alex Johns, whose family traces its roots back to those early herders. “Those Native Americans were my ancestors, and we’ve been raising cattle here ever since.”

Before European contact, bison had once roamed Florida, but by the 1500s, they had nearly vanished. To the Calusa, the arrival of cattle symbolized the return of the great grazing animals. Over generations, these herds evolved into the Florida Cracker cattle, now celebrated as the state’s official heritage breed.

By the 18th century, new tribes migrating south mingled with the remaining Calusa, giving rise to the Seminole Nation — a fusion of cultures that preserved the cattle-raising skills of their predecessors. Among the early Seminole leaders was the legendary Chief Cowkeeper, who reportedly owned over 1,000 head of cattle and supplied both sides during the American Revolution. Many modern Seminole ranchers still proudly call themselves “Cowkeepers” in his honor.

Survival and Revival

After decades of warfare with the U.S. government, most Native Americans were forced west on the Trail of Tears, but about 500 Seminoles, led by the medicine man Abiaka (Sam Jones), refused to leave. They survived deep within the Everglades, hidden with their herds, until the conflicts subsided.

In the 20th century, Seminole descendants began reclaiming their land — ultimately regaining 80,000 acres and federal recognition as a tribe in 1957. Through it all, they never abandoned their ranching roots.

The Modern Seminole Cattle Empire

In the 1920s, the Seminole Tribe founded a cooperative to strengthen their cattle operations. Today, that co-op includes 68 families managing 10,000 head of cattle, with women owning more than half of them. “We’re a matriarchal society; we go by our mother’s ancestry,” Johns explained. “Part of that is because of all the wars we fought — the men didn’t live very long.”

Now serving as the tribe’s executive director of agriculture, Johns oversees both co-op and private herds totaling about 500 cattle. Modern Seminole ranchers breed Brahman-Angus crosses, known for heat tolerance and strong growth — traits increasingly vital in a warming world.

A 500-Year Tradition, Still Thriving

What began as 20 stranded Spanish cattle has grown into a thriving, multigenerational industry that blends ancient tradition with modern innovation. The Seminole Tribe’s story is not only one of survival, but of enduring stewardship — proving that America’s oldest ranchers are still among its best.