Until the 1980s, people roamed the mountains of Shennongjia in central China, hunting monkeys for their meat and fur. Poor farmers were still clearing vast areas of forest, and as the environment around them collapsed, so did the local population of golden snub-nosed monkeys, which dropped to fewer than 500 individuals in the wild.

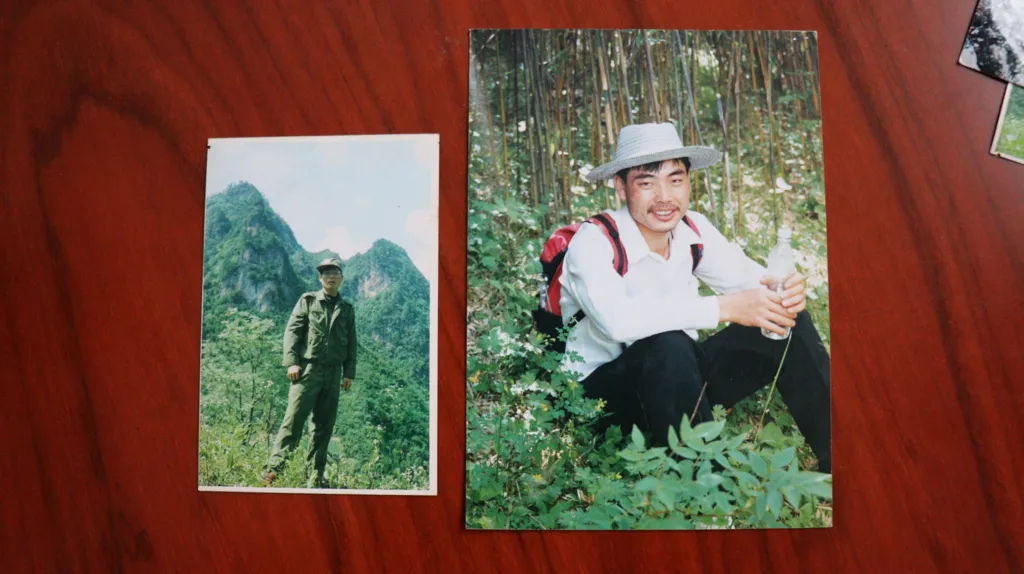

This was the situation when new graduate Yang Jingyuan arrived in 1991, still in his early 20s.

“The monkeys’ home was being destroyed by logging, so their numbers were going down fast,” he recalls. “Now it’s being protected, and the monkey figures are really improving.”

These days, Professor Yang is the director of the Shennongjia National Park Scientific Research Institute, and few people know this species better than he does. At 55, he has dedicated his entire career to studying and protecting this endangered subspecies of snub-nosed monkeys, which exist only in these mountains in Hubei province. He took us into the forest to meet them.

I asked if it was true that he now understood what many of their noises meant.

“Yes,” he said. “‘Yeeee’ is telling others the area is safe—they can come over. ‘Wu-ka’ means it’s dangerous. Be careful.”

Sure enough, as he made the various sounds, the monkeys came down from the trees, touching our hands and checking out the humans. Sitting on the ground to put them at ease, Prof Yang explained that these animals have a very complex social structure.

With baby monkeys jumping into my lap and crawling over us, Prof Yang described their group dynamics. One male, as head of a family group, might have three to five wives plus their children. Families come together to form larger bands that can exceed a hundred individuals. Bachelor males form separate groups and sometimes act as guards. Females have “affairs” outside their marriages, creating tension, and fights break out not only when a male takes over a family but also when entire tribes battle for control of territory.

Six-year-old females know when it’s time to leave their family to avoid inbreeding, and the animals—whose lifespan is around 24 years—also instinctively know when it’s time to die. Near the end of their lives, they find a secluded spot alone, and over decades, rangers have never found a monkey’s body after this occurs.

The ability of these unique animals to now survive across 400 square kilometres (155 square miles) marks a dramatic improvement from the past. Though the national park was established in 1982, Fang Jixi, a 49-year-old ranger who grew up in the area, explains that it took years for struggling farmers to stop destroying the environment.

“People were very poor in these mountains, and hunger was a real concern. There was no concept of protecting wild animals,” he said. “Even after logging was banned, there were still people illegally felling timber. If they didn’t cut down trees, how would they have money? Some were also secretly hunting to survive. Only after a long period of building awareness did the consciousness of local farmers change.”

Part of that awareness involved bringing farmers on board as protectors rather than destroyers of the forest.

“When the change occurred, it was the scientists who told us, ‘You can actually come and work with us. You can have a job here to help the animals,’” Mr Fang said. He now patrols the hills, keeping an eye out for poachers and monitoring the monkeys’ locations so researchers can study how and where they sleep, forage, and give birth.

Tracking the monkeys is no easy task—they can move across treetops in minutes, covering areas that would take a human an hour to traverse. Additionally, the monkeys are naturally wary of humans, especially given their history of hunting and disturbance.

The major push for preservation began in 2005, when Prof Yang and a small team formed a specialist study group. They spent an entire year gradually approaching a specific group of monkeys.

“They were very afraid of us at first. When they saw us from far away, they all fled,” Prof Yang said. But over months, the distance reduced—from 800 metres to 500 metres, then to 200 metres—until the animals allowed the team to be amongst them. “I was so excited because finally they had become my friends. Every day we could be together and communicating,” he added.

Old photos from the early days of Prof Yang’s team show bare hills with only about 60% tree cover. From a drone view today, reports of around 96% coverage appear accurate.

The park’s natural beauty has attracted millions of visitors, though dedicated monkey protection zones remain off-limits to all except approved staff. We were taken along a rugged mountain path in one of these zones, passing camera and transmitter equipment set up to observe not only monkeys but also black bears, boar, and many other species. From a breathtaking vantage point, we looked down on a valley where farmers once lived but have now been relocated to help protect the ecosystem.

One relocated resident shared that he was happy to leave behind a life of poverty. With government support, he now runs a guesthouse and feels much better off.

This effort has been challenging, particularly because female golden snub-nosed monkeys reproduce slowly, with one offspring every two years, and not all children survive. Yet the population has grown from fewer than 500 to more than 1,600 monkeys, with hopes of surpassing 2,000 within a decade.

“I’m very optimistic,” said Prof Yang. “Their home is now very well protected. They have food and drink, no worries about life’s necessities, and most importantly, their numbers are growing.”