In the quiet of his dorm room late at night, Huyen Hoang was on the cusp of slipping into slumber when a jarring image seized his thoughts—a photograph capturing the lifeless form of a dehorned rhinoceros in the heart of Vietnam.

It was in 2011 that Hoang, a Vietnamese American and a business major at Portland State University, was thrust into the world of rhino horn poaching. That very year marked the somber declaration of the extinction of the Javan rhino in his homeland, with rhinos globally succumbing to a relentless wave of poaching.

At the tender age of 21, Hoang, accompanied by his twin brother Huyen Hoang, who toiled part-time in a biotech lab, found themselves engrossed in an idea during a home visit—one that sought to challenge the status quo for rhino horn buyers.

“We both yearned for something audacious and impactful,” reflected Hoang, the business major.

In their final year, the Hoang brothers gave birth to Rhinoceros Horn LLC, envisioning the creation and sale of a lab-grown keratin—a synthetic counterpart to the coveted rhino horns. However, they weren’t solitary pioneers in this venture. In that same epoch, Ceratotech, a startup, stepped onto the scene, harboring dreams of cultivating life-size rhino horns using stem cells of the majestic species. Subsequently, in 2015, Pembient, a biotech firm, materialized with a mission to manipulate yeast cells into producing proteins mimicking rhino horns.

The endeavor to combat an age-old predicament with avant-garde technology captivated global imaginations, setting off a whirlwind of media attention. Substantial investments, reaching into the hundreds of thousands of dollars, flowed into the industry, giving rise to a plethora of prototypes scattered across labs in the United States.

Yet, nearly a decade later, the once-promising industry now dangles perilously on the precipice. Rhinoceros Horn LLC closed its doors in 2016, Pembient faces an impending shutdown this year, and Ceratotech, while still operational, grapples with the daunting challenge of securing funding for its ongoing research.

Even if these companies manage to defy the odds, they must confront mounting scrutiny from the 180-plus nations bound by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). This convention aims to safeguard endangered species from the perils of global trade.

So, what led to this unraveling? In candid interviews, the founders of these ventures revealed the Herculean task of disrupting the illicit rhino horn market through engineered alternatives—a feat laden with financial, logistical, and legal complexities.

In their audacious quest, these visionaries found themselves challenging age-old notions on how to preserve endangered species, unwittingly sparking a clash with an unconventional adversary—the very guardians dedicated to the rhinos’ protection.

“They viewed our efforts as unraveling the groundwork they’ve painstakingly laid and the programs they’ve meticulously executed,” Hoang revealed. “There was simply no space for us within the framework of their initiatives and proposed solutions.”

Conservationists woven into this narrative argue that the resistance was well-founded, characterizing the companies’ endeavors as, at best, well-intentioned but misguided, and at worst, a potentially perilous gamble.

“If you’re proposing to experiment with this cutting-edge technology, opt for a species that won’t face imminent extinction within a mere five years if something goes awry,” urged John Baker, the chief program officer of the conservation group WildAid. “There’s no room for error when dealing with endangered species.”

With the global rhino population dwindling to fewer than 27,000, rhino horns have ascended to the summit of the illicit wildlife trade, commanding staggering prices—up to $400,000 per kilogram, or roughly $11,000 per ounce—surpassing the value of elephant ivory and gold.

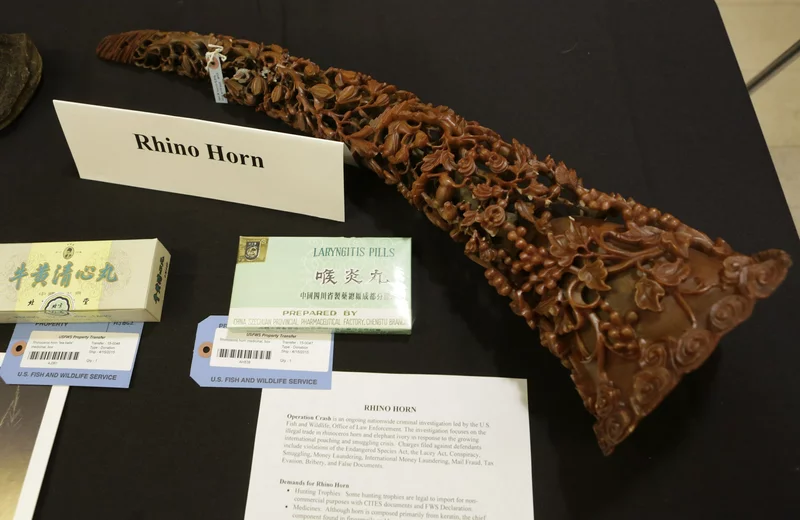

The epicenter of rhino horn markets resides in China and Vietnam, predominantly fueled by the affluent elite. Functioning as a symbol of status, horns undergo intricate carving, metamorphosing into opulent artifacts such as art pieces, jewelry, and decor. Despite a diminishing number of consumers subscribing to the belief that rhino horn shavings possess mystical medicinal properties for treating various ailments or hangovers, scientific evidence remains conspicuously absent. Keratin, the identical protein found in human hair and fingernails, fails to substantiate these purported benefits.

Back in the early 1900s, the world was home to around 500,000 rhinos, a thriving population documented by the World Wildlife Fund. Unfortunately, their numbers took a nosedive due to habitat loss and poaching.

To protect these creatures, global trade in rhino horns was banned in 1977 under CITES. However, this move unintentionally gave rise to a sophisticated poaching industry armed with helicopters and high-tech gear.

By 2022, the global rhino population had plummeted to just 27,000, with 561 rhinos falling victim to poaching in Africa, as reported by Save the Rhino International.

Enter the concept of lab-grown rhino horns, surfacing alongside breakthroughs in genetic engineering. Matthew Markus, CEO of Pembient, believed this technology could extend beyond livestock to benefit endangered species.

Looking back at the early days of his startup, Markus acknowledged some skepticism from the conservation field. Still, he didn’t expect it to be a complete nonstarter. “I didn’t think it would backfire or be a game-stopping issue,” he said. “I anticipated negative feedback, hoping that through ongoing discussions, we could eventually find common ground.”

In the beginning, people weren’t too thrilled with Markus’s idea of making synthetic rhino horn powder. Conservationists worried it might make folks think horn shavings had special healing powers. So, Markus switched gears and started focusing on creating solid, carved replicas of rhino horns.

But the pushback didn’t stop.

Markus’s big plan was to put lots of lab-grown horns on the market to lower the value of real ones. Yet, many conservationists argued this might actually make more people want the real deal. Critics were also worried about weird uses, like using the synthetic horns for iPhone cases or horn-infused beer, as Markus had suggested. There were even concerns that these copycat horns could make it harder for law enforcement to catch people smuggling real ones.

This clash wasn’t just about different opinions on tech and business; it was a clash of big ideas. Engineered rhino horns weren’t just seen as impractical by some; they were thought to threaten years of hard work in conservation. While wildlife groups had spent years busting myths and shining a light on rhino slaughter to reduce demand, the startups believed there could be a way for fake horns to coexist and offer a solution to the demand problem without hurting conservation efforts.

Pushing synthetic rhino horn products sends a message that using rhino horn is okay, as most people won’t really get the difference,” cautioned Baker from WildAid.

Some conservationists point to the 2008 legal sale of elephant ivory in China and Japan, a one-time event that studies suggest actually increased illegal ivory trade.

The two sides also clashed over whether rhinos should face any additional risks.

In the world of conservation, the precautionary principle takes center stage—an idea that demands significant risk reduction before adopting a new strategy or product. This belief holds that endangered species should be safeguarded using methods that have stood the test of time.

Baker highlighted Taiwan as an interesting case. Once Asia’s top consumer of rhino horns in the 1980s, today, demand in Taiwan is practically nonexistent. This transformation is credited to international pressure, local law enforcement, and a national campaign dispelling myths about the supposed medicinal value of rhino horns.

“We know it can work, but it takes time,” Baker affirmed, pointing to a substantial drop in poaching in recent years, contributing to the recovery of at least two rhino species—the black rhino and the greater one-horned rhino.

The critique against the profit-driven approach of these initiatives echoed loudly, drawing Tanya Sanerib from the Center for Biological Diversity into the fray. She underscored the worry that such endeavors reinforce the notion that “wildlife has to pay its way to stay.”

In the unfolding drama of 2016, wildlife groups urged a U.S. ban on lab-grown rhino horn sales. Peter Knights, then leading WildAid, accused entrepreneurs of playing a perilous profit game while turning a blind eye to the genuine threat faced by rhinos.

Despite widespread condemnation, the U.S. government passed the buck to CITES, casting shadows over potential investors and collaborators for Pembient, according to Markus.

The plot thickened in 2018 when Washington state investigations, ignited by the Humane Society groups, alleged illicit plans by Pembient to sell lab-grown rhino horn. No charges were pressed, and Markus clarified that the company was in the design phase, entertaining the use of cow stem cells if rhino cells faced prohibition.

While fines were absent, the investigations became a detour in Pembient’s journey. Humane Society International reaffirmed its dedication to upholding wildlife protection laws for the sake of rhinos.

In the arena of wildlife conservation, Rhinoceros Horn LLC and Ceratotech, like Pembient, found themselves entangled in a struggle for acceptance. Tanya Sanerib’s critique of the for-profit model echoed loudly, branding these endeavors as bearers of the controversial notion that “wildlife has to pay its way to stay.”

Post-college, the Hoang brothers, architects of Rhinoceros Horn LLC, faced an uphill battle. They sought to persuade merchants that their synthetic horn powder trumped the genuine article, championing environmental benefits and engineered health advantages. Their desire to partner with wildlife groups, seasoned in shaping rhino horn consumer behavior, hit a roadblock as conservationists adamantly opposed their product.

At Ceratotech, CEO Garrett Vygantas encountered hurdles in obtaining rhino cells. Zoo collaboration was elusive without the nod from conservationists. Eventually, they secured cells through private channels, overcoming a challenging initiation.

The landscape is marred by unanswered questions. While economic models by Professor Fred Chen hint at the potential of lab-grown horns as a conservation tool, Hoai Nam Dang Vu, a researcher, wears a more skeptical hat. Demand for real horns remains a formidable obstacle, and both researchers advocate for more comprehensive studies and tangible experiments.

The regulatory landscape shifted in 2022, with CITES members voting to regulate biotech products in alignment with endangered specimens. Ongoing discussions ponder the practical implementation of this decision. However, the rhino horn, whether real or fabricated, remains bound by a commercial trade ban under CITES.

Amidst the uncertainties, the story of the Shembe Church in South Africa stands as a rare real-world example. In a move to shield leopards, the church swapped real fur coats for synthetic ones in 2013, a conscientious shift away from endangering the wild cat.

A unique success story unfolded through a collaboration between wildlife group Panthera, faux-fur designers, and local church leadership. By partnering, they managed to halve the use of authentic leopard fur within a few years, preventing thousands of leopard deaths, according to Panthera.

As the narrative progresses, fundamental questions about human behavior, needs, and motives surface. How can deeply rooted beliefs about rhino horns in Vietnam and China be challenged? How do you deter South African poachers without alternative job options? And, crucially, how do you instigate care for a species distant and largely hidden from view, inspiring individuals to make decisions that benefit conservation?

The companies aiming to reshape conservation through technology envisioned a fast-track solution to these challenges. Over a decade later, this ambitious goal remains largely untested.

Ceratotech’s Vygantas envisions producing a life-size engineered horn within a year or two with adequate funding. However, he emphasizes that lab-grown horns will only succeed with the backing of conservationists; otherwise, they will continue to be treated as “contraband.”

Markus from Pembient, after attempts to form partnerships in South Africa, paused operations due to COVID-19. While the company has not produced a life-size horn, Markus refrains from labeling the endeavor a failure, emphasizing the importance of ongoing conversations about such innovative approaches.

The Hoang brothers, founders of Rhinoceros Horn LLC, haven’t discarded their initial product samples. Boxes of powdered keratin sit in their garage, unopened. Despite the company’s halt, they haven’t officially dissolved it, holding onto the hope that attitudes toward lab-grown horns may evolve.

Reflecting on their journey, one of the brothers notes the difficulty in trying to make the world better, leaving the question of why it’s challenging for each individual to ponder.