Beneath the warm waters off the coast of Tela, Honduras, lies a coral reef that’s astonishing marine scientists worldwide.

The Tela Bay reef should, by all accounts, be struggling or even dead, given the threats it faces: elevated water temperatures, boat traffic, agricultural runoff, and murky waters. Yet, this reef not only endures but flourishes—boasting a live coral cover of about 65%, nearly four times the Caribbean average of 18%.

Researchers are now racing to uncover why the Tela Reef seems impervious to these challenges and whether its secrets can be applied to other threatened reefs in the Gulf of Mexico.

One standout feature of Tela Reef is the presence of elkhorn coral, a species classified as Critically Endangered in the Caribbean. In Tela, however, extensive fields of elkhorn thrive despite conditions that have recently devastated its populations in the Florida Keys.

“If elkhorn is going to survive in Florida, it will need external assistance,” explained Andrew Baker, a marine scientist from the University of Miami. “This means introducing diversity, ideally from resilient populations adapting to similar conditions.”

Baker noted that Florida’s elkhorn corals are struggling with rising temperatures, so seeking resilient coral from warmer locales like Honduras could help develop future generations better equipped to handle climate change.

Several theories are being explored to explain the Tela Reef’s resilience:

- Saline Water Flushes: A local diver suggests that periodic influxes of highly saline water from the Gulf could kill off harmful bacteria and algae that typically smother coral reefs. While intriguing, this theory is challenging to validate scientifically.

- Fishing Practices: Another theory posits that the reef’s richness provides numerous hiding spots for small fish, deterring fishermen and thus protecting the reef’s ecosystem.

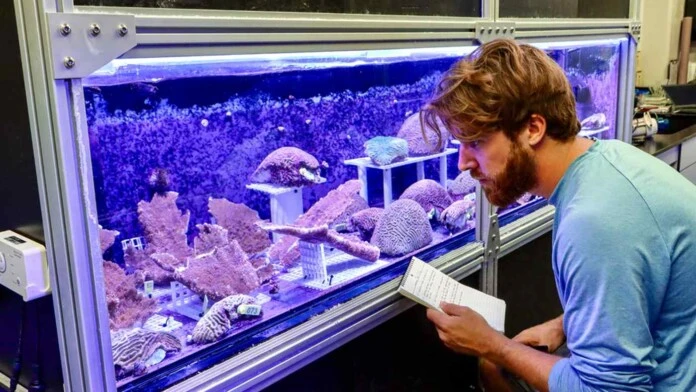

- Heat-Resistant Symbionts: A more compelling theory suggests that Tela corals host a unique strain of heat-resistant symbionts—microorganisms that live inside coral cells and help them through photosynthesis. Baker’s team at the University of Miami’s Coral Reef Futures Lab has found that the elkhorn corals from Tela are dominated by this unique symbiont, which could be crucial for their survival in warmer waters.

Additionally, Tela Bay is home to long-spined sea urchins, which were nearly wiped out by disease in the 1980s. These urchins graze on harmful algae, creating more space for coral growth. The interplay between the urchins and the corals adds another layer to the mystery.

“It’s a classic chicken-and-egg dilemma,” said Dan Exton, a coral reef ecologist. “Which came first: the high population of sea urchins or the abundant corals? The density of corals may also offer protection from predators.”

While the exact reasons behind Tela Reef’s success remain uncertain, scientists are not waiting for all answers. Tela Marine, a local coral breeding center, aims to propagate the genetic traits of Tela’s corals for global benefit.

The first step involves cross-breeding elkhorn corals from Tela with native Floridian corals at the University of Miami and the Florida Aquarium in Tampa.

“This is the first time scientists have imported corals from such warm reefs with the goal of creating offspring that can better tolerate heat,” Baker said. The breeding program has already seen success, with several Honduran elkhorn corals spawning and crossbreeding with Florida corals.

Keri O’Neil, director of the coral conservation program at the Tampa Aquarium, remains hopeful for continued success and future spawning later this summer.