Tim Friede, a truck mechanic from Wisconsin, has made a name for himself in the scientific community and beyond due to his shocking and extreme approach to medical research. For the past 20 years, Friede has subjected himself to hundreds of snake bites and venomous injections from some of the world’s deadliest snakes, including mambas, cobras, and vipers, in an effort to develop a groundbreaking anti-venom. His unorthodox method has led to the production of valuable antibodies in his blood, which have become the foundation for an experimental treatment aimed at combating the global issue of snakebite fatalities.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 100,000 people die from snake bites each year, with countless others suffering permanent disabilities due to the venom. While anti-venom exists, its production is limited, especially in rural or remote areas where snakebites occur most frequently. Moreover, the process of sourcing and creating anti-venom is complex and costly. Friede, however, through his risky self-experimentation, has managed to build a blood supply rich in antibodies that could potentially neutralize a wide variety of deadly snake venoms.

Friede’s work began out of childhood curiosity. He started playing with harmless garter snakes in his youth, and by the time he was an adult, he had transitioned to keeping and studying much more dangerous species. His fascination with venomous snakes grew, and in 1999, he began to extract venom from his pet snakes, dilute it, and inject himself with small amounts. He kept meticulous records throughout his experimentation, aiming to build immunity to the venom. Over time, Friede endured more than 200 snake bites and over 850 venomous injections, pushing his body to develop the resistance he sought.

Despite enduring a major hospitalization in 2001, when he was paralyzed and in a coma for four days after a particularly severe bite, Friede did not abandon his efforts. Instead, he doubled down on his experimentation. “In hindsight, I’m glad it happened,” he reflected. “I never made another mistake.” His dedication, while dangerous, provided an invaluable resource — blood filled with antibodies capable of neutralizing snake venom.

Enter Jacob Glanville, an immunologist and founder of Centivax, a biotech company focused on vaccine development. Glanville came across Friede’s videos documenting his self-immunization and was astounded by what he saw. He realized that Friede might have the very antibodies needed to develop a universal anti-venom. Glanville reached out to Friede, and soon Friede became the director of herpetology at Centivax, where his blood was used to create a new treatment for snakebites.

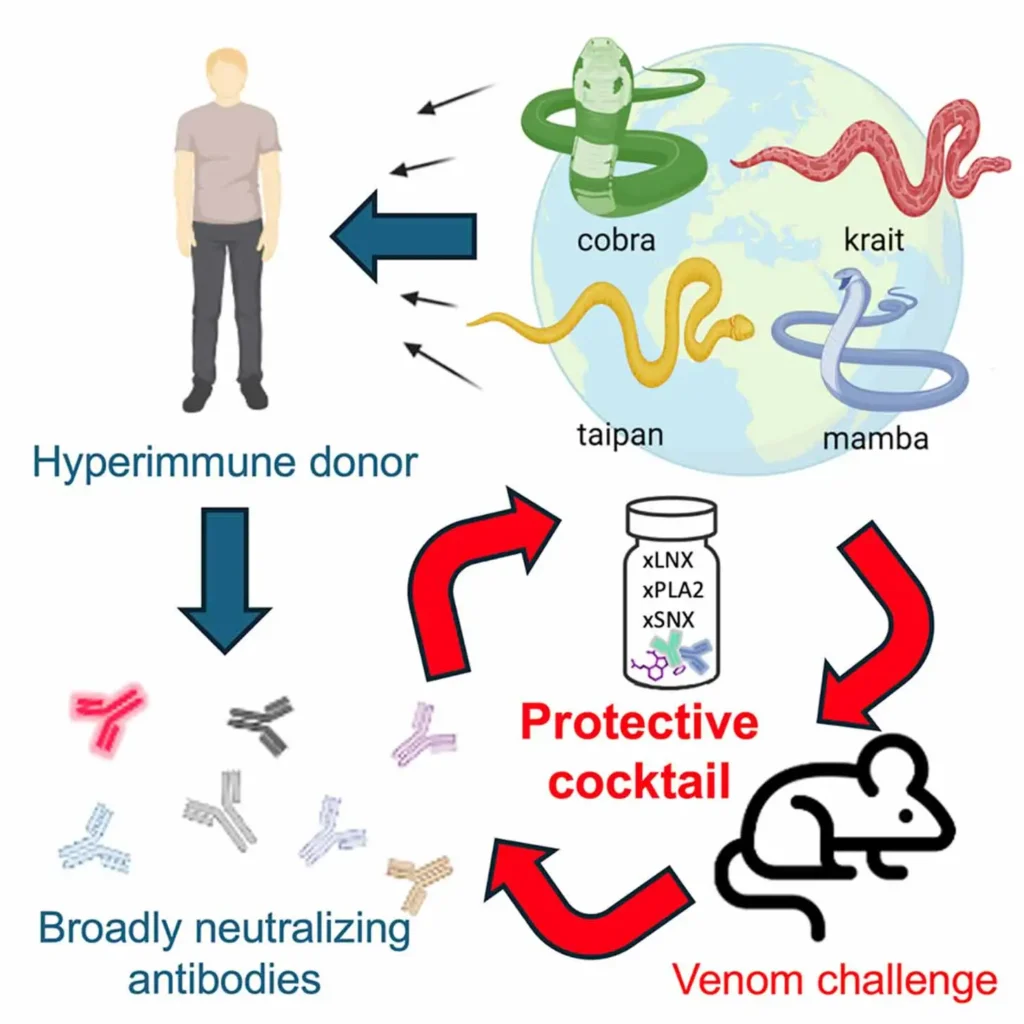

Centivax’s research focused on 19 species of snakes from the elapid family, which includes some of the deadliest snakes in the world. Elapids kill by injecting neurotoxins into their prey, paralyzing muscles and potentially causing death by suffocation, as they target vital organs like the heart and lungs. Each elapid species has a slightly different neurotoxin, meaning that traditional anti-venoms would have to be tailored to each snake, making them ineffective for use across species.

However, Friede’s blood, after years of exposure to these snakes’ venom, contains fragments of each of the toxins from these species, as well as the antibodies required to neutralize them. These antibodies prevent the toxins from binding to human cells, mitigating their harmful effects. With this treasure trove of data and blood, Glanville’s team at Centivax worked to develop a pan-anti-venom that could treat bites from multiple species of venomous snakes. This new serum combines Friede’s antibodies with compounds like LNX-D09, SNX-B03, and varespladib, a molecule that inhibits venom toxins.

In recent studies published in the journal Cell, Centivax successfully created a serum capable of neutralizing toxins from 19 different snake species. The next step for researchers is to test this serum in real-world scenarios. Trials will begin with treating dogs that have been bitten by snakes in Australian veterinary clinics. If the results are positive, human clinical trials will follow. One of the added benefits of this human-derived serum is that it is believed to lower the risk of allergic reactions, which is a common concern with animal-derived anti-venoms.

Professor Peter Kwong of Columbia University, who was a senior author on the study, remarked that this new anti-venom could potentially take the form of a single pan-anti-venom cocktail that would be effective against both elapids and viperids, another family of venomous snakes. This could revolutionize how snakebites are treated around the world, especially in regions where anti-venom access is limited.

Friede, who has now stepped away from further self-experimentation — his last snake bite was in November 2018 — remains deeply proud of the impact his work could have on saving lives. “I’m really proud that I can do something in life for humanity,” Friede said. “To make a difference for people that are 8,000 miles away, that I’m never going to meet, never going to talk to, never going to see, probably.”

In the end, Friede’s extreme dedication to science and his fascination with snakes have led to a potentially life-saving breakthrough. His willingness to risk his life for the sake of understanding venom and building immunity has helped pave the way for a new generation of anti-venom treatments that could one day save countless lives around the world.