Animals are disappearing too fast for researchers to record all of the extinctions we’ve caused.

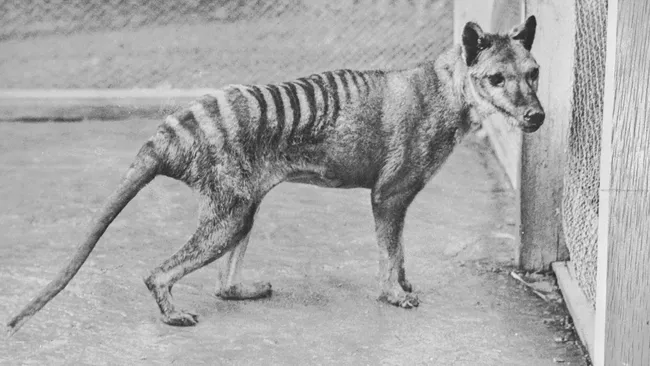

Humans are notably effective at driving wildlife to extinction. From golden toads to Tasmanian tigers, many species have fallen victim to our impact. But how many animal species have humans truly driven to extinction?

Determining the exact number is challenging and estimates can vary. However, it could be in the hundreds of thousands.

Starting with confirmed extinctions, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List reports that 777 animal species have gone extinct since the modern era began around 1500. While some extinctions might have occurred naturally, human activities have likely played a significant role in most, if not all, of these cases, particularly given our profound impact on nature over the past 500 years. Although human-induced extinctions began thousands of years ago, before 1500, precise records are sparse, so the focus is often on the last 500 years.

The IUCN has assessed the extinction risk of only about 5% of the world’s known species, suggesting that many extinctions may not yet be recorded. A 2022 study published in Biological Reviews estimated that between 150,000 and 260,000 species could have perished since roughly 1500.

These numbers were so surprising that they startled the study’s lead author, Robert Cowie, a research professor at the University of Hawaii. “I thought, jeez, have I made some mistakes in the calculations?” Cowie remarked.

Cowie hadn’t made a mistake, but his estimates came with significant caveats. To arrive at the figure, his team sampled 200 land snails and, using previous scientific studies and expert consultations, determined how many of these snails had gone extinct. They then extrapolated this data to estimate how many species might have gone extinct if all known species had experienced a similar extinction rate consistently over 500 years.

The calculated extinction rate was 150 to 260 extinctions per million species-years (E/MSY) — in other words, 150 to 260 extinctions each year for every million species on Earth. Cowie also examined extinction estimates for other wildlife groups, including amphibians and birds, which ranged from 10 to 243 E/MSY. However, there was a consensus around a more moderate figure.

“They tend to cluster around about 100 [E/MSY],” Cowie said. “I think that’s a more reasonable, not overly conservative, but not overly exaggerated value.”

Mystery Math

Applying a rate of 100 E/MSY to Cowie’s 2022 method suggests that approximately 100,000 of the roughly 2 million known species may have gone extinct over the past 500 years. However, this figure does not account for unknown animal species.

A 2011 study published in PLOS Biology estimated that there are around 7.7 million animal species. Using this figure and assuming a rate of 100 E/MSY over 500 years — while subtracting the 3,850 animals that would be expected to naturally go extinct with a background extinction rate of 1 E/MSY — leads to an estimate of 381,150 animal extinctions caused by humans. This is a rough estimate and should be viewed with caution.

Grain of Salt

John Alroy, an associate professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at Macquarie University in Australia, is working to quantify diversity and extinction. He has expressed skepticism about the ability to accurately calculate modern extinction rates.

“We should be supercautious about trying to nail a number down based on the existing literature,” Alroy said. “My feeling is that we don’t have a very good fix on the current extinction rate whatsoever.”

To understand the overall extinction rate, researchers need to know how many species there are in the first place, according to Alroy. Much of the world’s wildlife remains unknown to science, and species are often concentrated in understudied regions, such as the tropics. Additionally, insects, which represent the most species-rich group, are less studied compared to larger animal groups like mammals and birds. Alroy proposed that researchers use museum data for representative animal groups and track how many species they lose over time to estimate extinction rates. “You’d want to know how many species did you have before, [and] how many species did you have after,” Alroy said.

Regardless of the exact rate, Alroy emphasizes that humans are exacerbating the extinction crisis, and the number of extinctions is likely much higher than the 777 recorded on the IUCN Red List.

The broad range of E/MSY estimates from various studies all share a common theme: they are significantly higher than the natural background rate. This indicates that human activities are severely impacting Earth’s biodiversity. “Whether the extinction rate is 100 E/MSY or 20 E/MSY or 200 E/MSY, it’s still a lot, and it’s still really bad,” Cowie noted.