Warm temperatures, not just predator pressure, may favor long, bat-fooling streamers

Biologists Link Luna Moths’ Streamer Tails to Stable Climates

For the first time, biologists have connected the long, ribbon-like tails trailing from the hind wings of luna moths to an unexpected factor: a consistently warm climate.

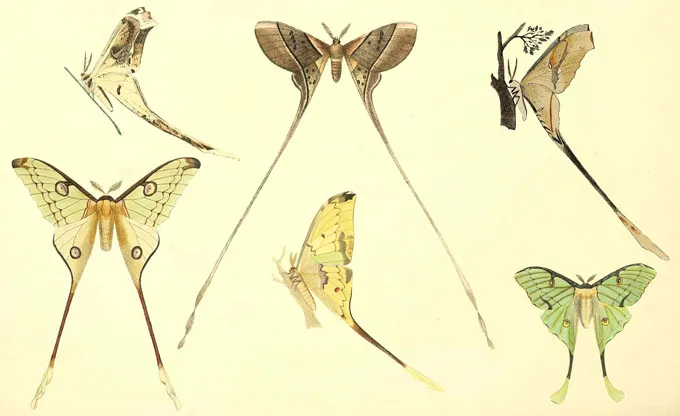

These dangling wing appendages are among the more whimsical curiosities of evolution—akin to the narwhal’s unicorn-like tusk or the peacock’s ornate feather train. Wing streamers, often with curled or cupped tips, have evolved independently at least five times within the Saturniidae family, which includes luna and other “moon” moths, according to behavioral ecologist Juliette Rubin of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Balboa, Panama. In a new study published May 7 in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, Rubin and colleagues analyze environmental data and find a correlation between these tails and habitats with long stretches of stable temperatures.

Moon moths, Rubin notes, can develop wings large enough to span a human palm and often boast striking colors. However, this adult stage is fleeting—lasting just about a week, during which the moths court and reproduce.

Previous research by Rubin showed that the tails are not essential for attracting mates. Instead, they serve a defensive role: confusing echolocating bats. “I’ve always been fascinated by this ancient evolutionary arms race—between a predator using sonar to hunt at night and a prey species evolving tricks to survive in that dark sky,” Rubin says.

Unlike some moths, luna moths can’t detect the sonar clicks of hunting bats, nor do they emit any warning sounds. Instead, their fluttery tails often mislead predators, diverting attacks toward expendable tissue rather than vital body parts.

Despite their size, the streamers don’t appear to hinder flight—though Rubin notes more testing is needed to rule out subtle aerodynamic costs. The real evolutionary trade-off may lie in the developmental resources required to grow such elaborate wings.

To explore this idea, Rubin and her team turned to citizen science, analyzing luna moth photos uploaded to iNaturalist. They used antenna length to standardize body size across specimens and mapped where long tails were most common.

Unsurprisingly, regions with high populations of insectivorous bats showed a greater incidence of long tails. But another key factor emerged: warm climates with minimal seasonal variation. In such environments, larvae can feed longer and more efficiently, allowing them to store the energy needed to grow extravagant wings for their brief but spectacular adult phase.