Monarchs are the only insects to attempt such a massive trek as the one from Canada to Mexico—and the success of this butterfly’s 3,000-mile journey may come down to how many white spots are on their wings.

A new study by University of Georgia researchers suggests that the butterflies with more white spots are better at reaching their long-distance wintering destination.

Although it’s not yet clear how the spots aid the species’ migration, it is believed the spots change airflow patterns around the wings.

For thousands of years, the orange-winged wonder has been traversing North America to spend the winter in oyamel fir trees in the mountain forests in south and central Mexico.

How an animal with a brain the size of a poppy seed navigates to this one special place has baffled ecologists for decades.

“We undertook this project to learn how such a small animal can make such a successful long-distance flight,” said lead author Andy Davis, an assistant researcher in the University’s Odum School of Ecology. “We actually went into this thinking that monarchs with more dark wings would be more successful at migrating because dark surfaces can improve flight efficiency. But we found the opposite.”

“It’s the white spots that seem to be the difference maker,” Davis said.

The researchers analyzed nearly 400 wild monarch wings collected at different stages of their journey, measuring their color proportions. They found the successful migrant monarchs had about 3% less black and 3% more white on their wings.

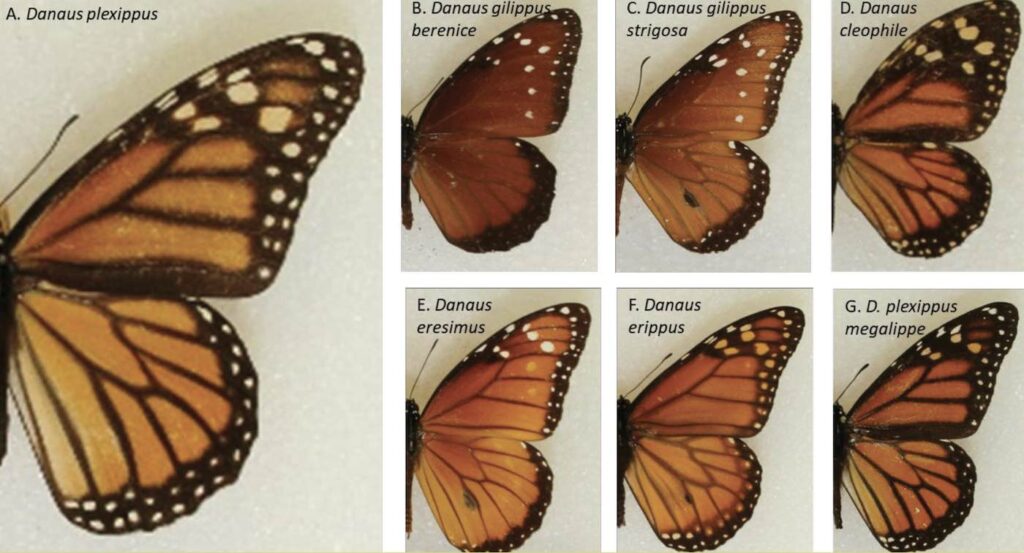

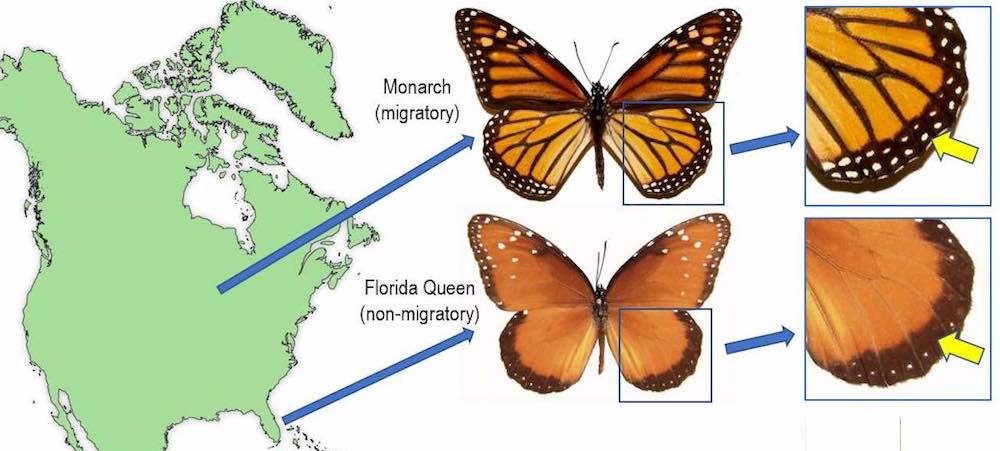

An additional analysis of museum specimens that included monarchs and six other butterfly species showed that the monarchs had significantly larger white spots than their non-migratory cousins.

The only other species that came close to having the same proportion of white spots on its wing was its semi-migratory relative, the southern monarch.

The coloring is related to the amount of light and heat they receive during their journey. More white spots means less exposure to the sun’s radiation.

“The amount of solar energy monarchs are receiving along their journey is extreme, especially since they fly with their wings spread open most of the time,” Davis said. “After making this migration for thousands of years, they figured out a way to capitalize on that solar energy to improve their aerial efficiency.”

But as temperatures continue to rise, altering the solar radiation reaching Earth’s surface, monarchs will likely have to adapt to survive, said Mostafa Hassanalian, co-author of the study and an associate professor at the New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology.

But it’s certainly not all bad news for the flying insects.

Davis’ previous work showed that summer populations of monarchs have remained relatively stable over the past 25 years. That finding suggests that the species’ population growth during the summer compensates for butterfly losses due to migration, winter weather and changing environmental factors.

“The breeding population of monarchs seems fairly stable, so the biggest hurdles that the monarch population faces are in reaching their winter destination,” Davis said. “This study allows us to further understand how monarchs are successful in reaching their destination.”

The study, sub-titled “How the monarch got its spots,” was published in PLOS ONE.