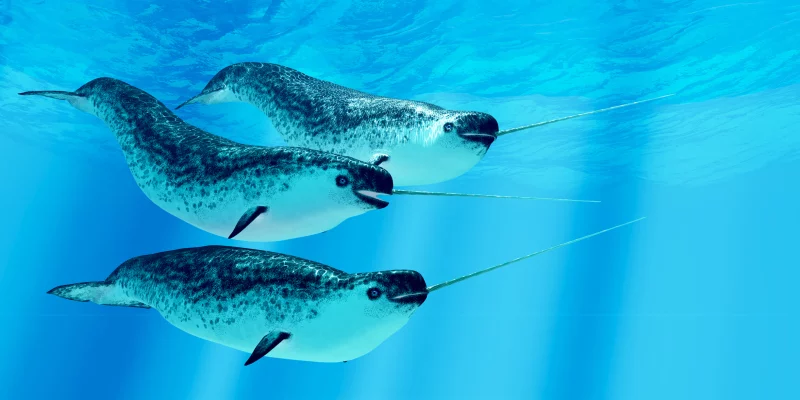

Narwhals May Use Their Famous Tusks to Hunt Fish, New Research Suggests

The long, spiraled tusks of narwhals might serve more than just a decorative or mating purpose — they could also help these Arctic whales stun or capture prey, according to new insights from researchers who have monitored them via drone footage.

For the first time, scientists have observed narwhals using their tusks to strike and manipulate fish, possibly as a hunting technique. In the drone recordings, narwhals were seen repeatedly tapping fish with their tusks, although experts remain divided on what this behavior truly signifies.

A study published in Frontiers in Marine Science claims this is “clear evidence” of narwhals actively chasing fish and using their tusks to influence the prey’s movement. According to Cortney Watt, a researcher with Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the University of Manitoba, this behavior suggests tusks could aid in catching fish.

Still, Watt emphasizes that tusks aren’t necessary for survival, as females — who typically lack tusks — are able to hunt and feed effectively. “I wouldn’t say it’s a critical feeding adaptation, but rather an additional tool some narwhals may have learned to exploit,” Watt explains.

However, some experts remain cautious about drawing firm conclusions from limited footage. Kristin Laidre, a polar scientist at the University of Washington, points out that these are brief clips showing a handful of narwhals near the surface. “Whether they’re playing or actually attempting to catch fish is still unknown,” she says.

A Closer Look at the ‘Unicorns of the Sea’

Narwhal tusks, which can grow up to ten feet long, have intrigued scientists for centuries. Greg O’Corry-Crowe, a zoologist at Florida Atlantic University, has had the rare chance to handle a live narwhal while fitting it with a satellite tracker. “Holding a narwhal and feeling that tusk is incredible,” he says. “It looks like a finely carved spiral, almost like something crafted by hand.”

Historically, sailors once sold these tusks as “unicorn horns,” feeding legends of mythical creatures. And while it’s well-documented that males use tusks to compete for mates — longer tusks signaling strength and fertility — O’Corry-Crowe, who helped capture the recent drone footage, suggests there may be more to the story.

When researchers flew drones over narwhals socializing in clear Arctic waters, they noted calm behavior among the animals. Males gathered in bachelor groups while females cared for calves. Some tusked narwhals appeared to play with fish like Arctic char, flipping them with their tusks and even passing them between one another — possibly as a form of social learning.

“They would toy with a fish, give it a tap, then turn to another narwhal as if to say, ‘Your turn,'” says O’Corry-Crowe. Sometimes the tusks seemed to stun fish, while at other moments, the behavior appeared curious rather than predatory.

“The way they used their tusks was surprisingly delicate — more like a surgical tool than a weapon,” he adds.

Mysteries Below the Ice

Cortney Watt notes that differences in the diets of male and female narwhals have raised questions about the tusk’s role in foraging.

Past studies have suggested narwhals may swim upside down along the seafloor, potentially using their tusks to stir up hidden prey. And in 2017, another group of researchers filmed narwhals seemingly hunting Arctic cod with their tusks, leading to speculation that the mystery of tusk use had been solved.

But Kristin Laidre emphasizes that tusks are primarily a sexual characteristic, with abundant evidence supporting their role in mating displays. “There’s little doubt among scientists that tusks are sexual traits,” she asserts. “The idea that there’s a big mystery left about tusk function is overstated.”

Still, much about narwhal life remains unknown. These whales spend the majority of their time deep beneath Arctic ice, often diving a mile or more in pursuit of prey. Observing them in their natural, deep-water environment remains a major challenge.

“If only we could get cameras or sensors that could follow them into those depths — imagine what we could learn,” Laidre reflects. “It would be groundbreaking, but also incredibly hard to achieve.”