As the early morning sun casts a gentle glow over the San Gabriel Mountains, we find ourselves standing in a nondescript dirt parking lot at Bear Divide. Surrounding us, the hills are cloaked in chaparral vegetation, and the sprawling metropolis of Los Angeles lies just to the south. At first glance, this may seem like any other trailhead in the greater LA area.

However, we’ve come to Bear Divide for a truly extraordinary reason: it’s one of the few places in the western United States where you can witness the spectacle of bird migration during daylight hours.

As our NPR team gathers, our eyes turn to Kelsey Reckling, a PhD student at UCLA who specializes in the study of bird migration. With focused determination, she scans the horizon, her keen eyes searching for any sign of avian activity.

Bear Divide holds a special significance in the world of ornithology. Serving as a passageway through the imposing barrier of the San Gabriel Mountains, it acts as a natural funnel for migrating birds. Here, they fly at a low enough altitude for researchers like Reckling to identify, capture, and study them as they make their journey.

According to Reckling, on an exceptional day, the skies above Bear Divide are alive with the mesmerizing sight of thousands upon thousands of birds in flight. As they embark on their northward journey for the summer months, up to 20,000 of these winged travelers can be observed zooming by in a breathtaking display of migration.

It’s a testament to the remarkable natural phenomena that unfold in seemingly ordinary places, reminding us of the awe-inspiring beauty and complexity of the world around us. And here, amidst the rugged beauty of the San Gabriels, we’re granted a front-row seat to one of nature’s most captivating spectacles.

Since its discovery as a migration hotspot in 2016, Bear Divide has become a magnet for bird enthusiasts like Reckling, who are eager to witness a fleeting moment in the epic journey of migration. Here, amidst the tranquil beauty of the San Gabriels, birdwatchers gather to catch a glimpse of winged travelers embarking on a remarkable odyssey.

Today, we stand witness to a phenomenon of staggering proportions. Some of the birds we’ll encounter have traveled thousands of miles, journeying from as far as South America to their breeding grounds in Alaska. As the sun rises, signaling the start of the avian procession, a symphony of chirps fills the air, breaking the serene silence of the valley.

With practiced precision, Reckling identifies each passing bird, recording their species and numbers on a tablet. These meticulous observations contribute to a comprehensive database of bird sightings, which researchers like Reckling and her colleagues utilize to study not only individual species but also broader trends in the natural world.

Ian Davies, from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, emphasizes the importance of understanding bird behavior as a barometer for broader environmental changes. “You know the canary in the coal mine saying?” he remarks. “If we understand what’s happening to birds, we might be able to grasp broader changes in the environment, in climate, and other crucial aspects.”

Indeed, the birds serve as sentinel species, offering valuable insights into the health of ecosystems and the impact of human activities on the natural world. By unraveling the mysteries of migration and monitoring avian populations, researchers like Reckling and Davies play a vital role in safeguarding our planet’s biodiversity for generations to come. And here, at Bear Divide, we are privileged to witness firsthand the intricate interplay between nature’s wonders and humanity’s quest for understanding.

Davies has journeyed across the country for this momentous occasion, standing shoulder to shoulder with Reckling, armed with a trusty pair of binoculars. With practiced expertise, he calls out bird species, guiding Reckling as she swiftly enters each sighting into the database.

For the untrained eye, spotting these elusive avian travelers can be a daunting task. The birds flit by with remarkable speed, their diminutive forms making them a challenge to discern amidst the landscape. Yet, with a keen eye and an ear attuned to nature’s melodies, Reckling and Davies effortlessly identify each fleeting visitor. Sometimes, it’s the bird’s song alone that gives away its identity.

As a Townsend’s warbler darts past, followed by a hermit warbler and a lark sparrow, I find myself missing every fleeting glimpse. Before I can even register their presence, they vanish into the vast expanse of the sky.

“That’s the nature of this place, and many others like it,” Davies remarks with a wistful smile. “You’re granted just a brief moment, a mere second, to witness something truly beautiful. But in that fleeting moment, the world reveals its wonders. Blink, and you’ll miss it.”

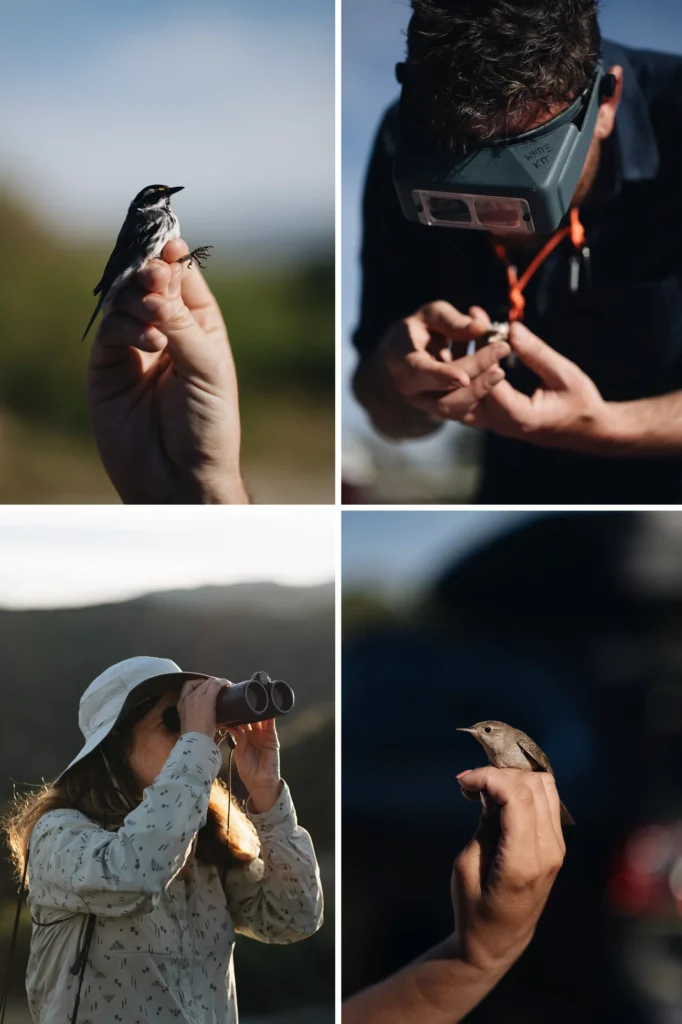

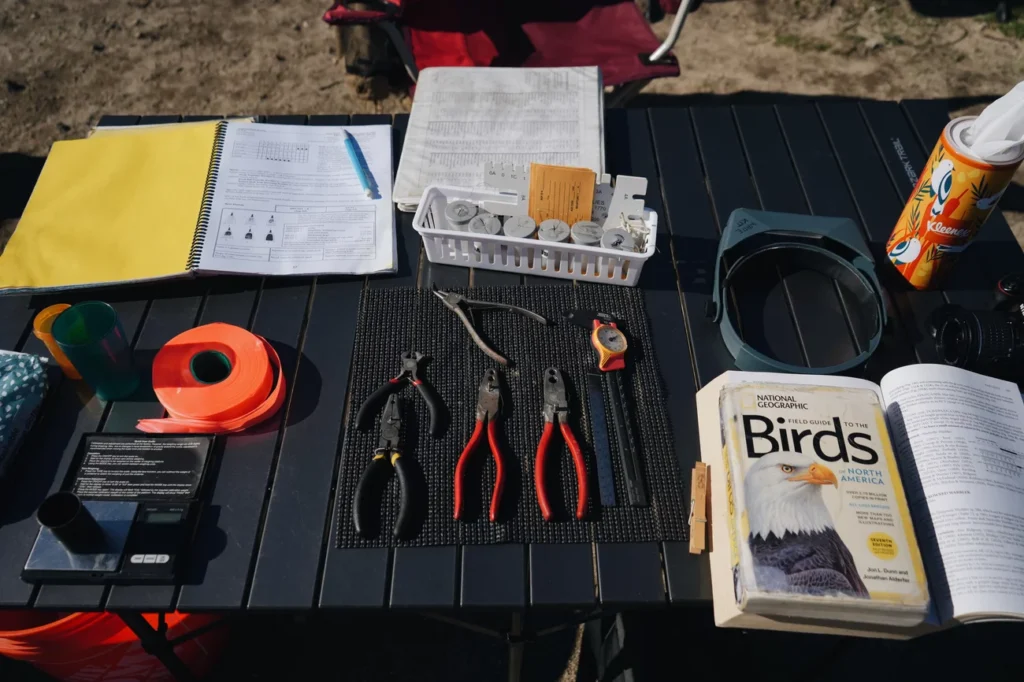

While Reckling and Davies keep watch overhead, another team of researchers works tirelessly just a few hundred feet away. Led by Lauren Hill, a graduate student at Cal State LA, they oversee the banding station at Bear Divide—a hub of scientific activity where birds are captured, tagged, and meticulously measured.

As the birds flit through the brush, some find themselves ensnared in nearly invisible mesh nets strategically placed by the researchers. With precision and care, Hill begins the intricate process of examining one of the captured birds up close, offering a glimpse into the inner workings of avian life that few are privileged to witness.

“This is a house wren,” Hill declares softly, her voice carrying a note of reverence as she cradles the delicate bird in what’s known as a bander’s grip, its head gently secured between her middle and index fingers.

With meticulous care, she affixes a tiny bracelet bearing a unique nine-digit identification number to the bird’s ankle, likening it to a social security number for our feathered friends. As she proceeds to measure the bird’s wing length and weight, inspecting the condition of its feathers and assessing its reproductive readiness, a sense of profound respect for the intricacies of nature pervades the air.

After tenderly scrutinizing the bird for a few minutes, Hill releases it back into the wild, allowing it to continue its journey unhindered.

Beyond the scientific imperative of building a comprehensive database to monitor the health of bird populations traversing Bear Divide, the banding station serves a broader purpose—one of accessibility and community engagement.

“In science, there’s often a sense of gatekeeping,” reflects Hill. “But here, we strive to break down those barriers and create an environment that welcomes everyone—whether they’re seasoned birdwatchers or simply curious passersby. We encourage anyone with a love for nature to join us, to ask questions, and to share in the wonder of discovery.”

As we observe the banding station in action, a diverse gathering of hikers, families, and avid bird enthusiasts congregates around another researcher, captivated by the sight of an orange-crowned warbler held gently in their hands.

Tania Romero, a fellow graduate student at Cal State LA, stands at the helm of the banding station alongside Hill, embodying the spirit of inclusivity and knowledge-sharing that defines this remarkable scientific endeavor.

As the morning progresses and bird sightings gradually dwindle, we make our way back to Reckling for a final recap and tally of the day’s observations.

“Lots of different warblers, some buntings, a few orioles,” Reckling reports with a satisfied smile. “In total, we’ve counted over 850 birds this morning.”

It’s a testament to the richness of biodiversity that thrives within the San Gabriel Mountains and the vital role that Bear Divide plays as a migratory hotspot. Each bird observed is a testament to the resilience and adaptability of these avian travelers, as well as a reminder of the interconnectedness of all living beings.

For Romero, whose journey from south LA to becoming a graduate student studying birds reflects a deeply personal connection to the natural world, this experience is especially meaningful. Reflecting on her own upbringing, she acknowledges the importance of accessibility and representation in science.

“When I was growing up in south LA, I wished I had this kind of access to scientists,” Romero shares candidly. “I had no idea that science could be a career option for city kids like myself. It wasn’t until my last year in undergrad that I even considered studying birds for a living. For the longest time, I felt like I didn’t belong in this world—that it wasn’t meant for someone like me.”

Yet, as she stands amidst the rugged beauty of Bear Divide, leading the banding station and sharing her passion for ornithology with others, Romero embodies the transformative power of accessibility and inclusion in science.

As our day draws to a close, filled with the wonder of avian migration and the camaraderie of scientific exploration, Reckling’s words ring true: “I’m happy with today.” And indeed, in this fleeting moment, surrounded by the majesty of nature and the warmth of community, there is much to be grateful for.