In Hong Kong, a pair of giant pandas is set to depart for the U.S. from China, marking a revival of “panda diplomacy,” a strategy that has historically sent these beloved bears worldwide to bolster foreign relations and showcase Chinese cultural influence.

However, not everyone is pleased with this decision.

An impassioned online community of panda enthusiasts in China and beyond has fervently embraced these black-and-white icons, which are revered as national symbols. Their devotion often mirrors the fervor typically reserved for pop stars and celebrities, occasionally escalating to toxic levels.

Criticism has surfaced following announcements that China will dispatch a pair of pandas to the San Diego Zoo, expected to arrive this week, and another duo to the National Zoo in Washington by year’s end. Some critics have gone so far as to disclose personal information about the pandas’ caretakers online.

Concerns about animal welfare feature prominently among dissenting voices, though such claims lack substantiation. Additionally, nationalist sentiments have fueled opposition, particularly amid strained U.S.-China relations over trade, technology, and Taiwan.

On Chinese social media platform Weibo, calls to halt panda diplomacy altogether have gained traction, with some viewing the program as a symbol of weakness and potential loss of national pride. “Given the current tensions with the U.S., why rush to send our national treasures into potential jeopardy?” questioned one commenter last month.

The recent flurry of panda deals between China and various U.S. zoos has stirred up significant online concern, partly fueled by the unfortunate death of Le Le, a male panda who had resided at the Memphis Zoo since 2003. His passing in February 2023 due to heart disease at the age of 24 sparked outcry among Chinese internet users. Many questioned the circumstances surrounding his death and expressed worries about the well-being of his partner, Ya Ya.

Claims surfaced alleging that Ya Ya suffered from malnutrition and excessive confinement, further exacerbated by reports of patchy fur due to a chronic skin condition. Despite official statements from both Chinese and U.S. officials dismissing these concerns, Le Le’s fans remained skeptical. Calls for Ya Ya’s return to China intensified, especially as the zoo’s 20-year loan agreement for the pandas had already expired.

In November, the National Zoo in Washington returned its three pandas to China as their loan agreement concluded after 20 years. This move left Zoo Atlanta as the sole host of pandas in the U.S., raising apprehensions about the future of the longstanding panda diplomacy initiative, which had symbolized U.S.-China relations since 1972.

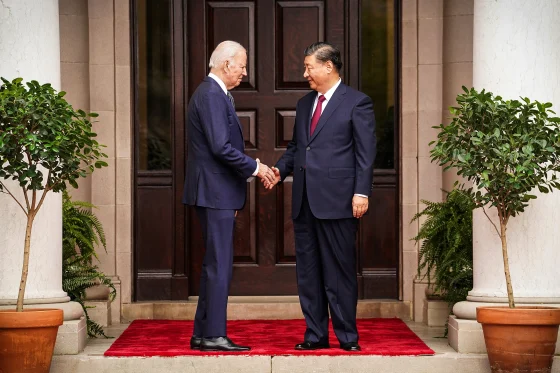

However, tensions eased when Chinese President Xi Jinping hinted at additional panda agreements during a visit to California in November. Subsequently, Beijing announced new panda deals with the National Zoo, San Francisco Zoo, and San Diego Zoo, which will receive its first pandas since 2019 — 4-year-old male Yun Chuan and 3-year-old female Xin Bao.

Beyond the geopolitical significance, pandas enjoy immense popularity in China and abroad, drawing crowds to zoos and amassing online followings. Enthusiastic fans join virtual communities dedicated to specific pandas, such as He Hua from the Chengdu Panda Base, who boasts over 870,000 followers on Weibo. These communities engage daily through livestreams and social media, organizing events and campaigns to support their favorite pandas.

However, extreme fandom occasionally leads to controversies, such as disputes over treatment and facilities at panda bases. For instance, a video showing He Hua falling while playing with her sister sparked debates among fans, highlighting concerns over animal welfare and facility conditions.

Despite these challenges, pandas continue to captivate global attention, serving as cultural ambassadors and symbols of conservation efforts worldwide.

Extreme panda fandom extends far beyond China, as illustrated by the case of Fu Bao, South Korea’s first naturally bred panda. Born in 2020 in Yongin, Fu Bao gained immense popularity, with a single video on Everland theme park’s YouTube channel amassing over 26 million views, surpassing all others.

In April, Fu Bao departed South Korea for China as per regulations for pandas born overseas. However, allegations of mistreatment surfaced in South Korea following her relocation to a panda reserve in Sichuan province. Despite Chinese officials sharing photos and videos confirming Fu Bao’s good health, concerned Korean fans mobilized a social media campaign to “save Fu Bao” and “return Fu Bao,” even placing an ad in Times Square, New York.

Some zealous Fu Bao supporters in China escalated tensions by harassing panda experts and keepers in Sichuan, uploading photos online to provoke cyberbullying incidents.

Gary Hsu, a 24-year-old graduate student from Jiangsu province and a panda enthusiast, expressed frustration with the extreme aspects of panda fandom. “Toxic panda fans often lack independent thinking,” he remarked to NBC News. “Regardless of which country’s zoo pandas are sent to, their statements can be incomprehensible.”

Pandas evoke a deep human desire to nurture and protect, noted Chee Meng Tan, an expert in Chinese foreign policy and soft power at the University of Nottingham Malaysia. This sentiment is amplified when pandas are viewed as national symbols. For some Chinese fans, any perceived harm to a panda can be interpreted as an attack on the nation and its people.

Tan emphasized that extreme efforts by fans to keep pandas within China are unlikely to sway China’s international image-building efforts. “Chinese authorities understand that their furry ambassadors are unparalleled in terms of soft power,” he explained, underscoring the enduring global appeal and diplomatic significance of these iconic animals.