Columbian mammoths in Mexico are genetically different from those in the U.S. and Canada, surprise DNA study reveals.

For the first time in tropical latitudes, scientists have successfully sequenced ancient DNA from the Columbian mammoth (Mammuthus columbi), the only mammoth species native to North and Central America. The results uncovered unexpected genetic differences that set Mexican mammoths apart from their northern relatives — raising new questions about how these Ice Age giants evolved.

Standing nearly 13 feet (4 meters) tall, Columbian mammoths dwarfed their woolly cousins and roamed from Canada to Central America. Fossils are plentiful, but their evolutionary history has remained murky.

That began to change in 2019, when construction of Mexico’s Felipe Ángeles International Airport revealed a massive Pleistocene graveyard, with remains of more than 100 Columbian mammoths. The sheer scale of the find caught the attention of Federico Sánchez-Quinto, a paleogenomicist at UNAM, who launched a project to recover DNA from the remains.

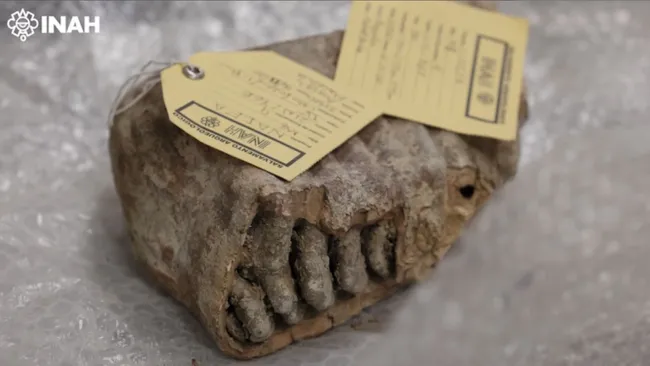

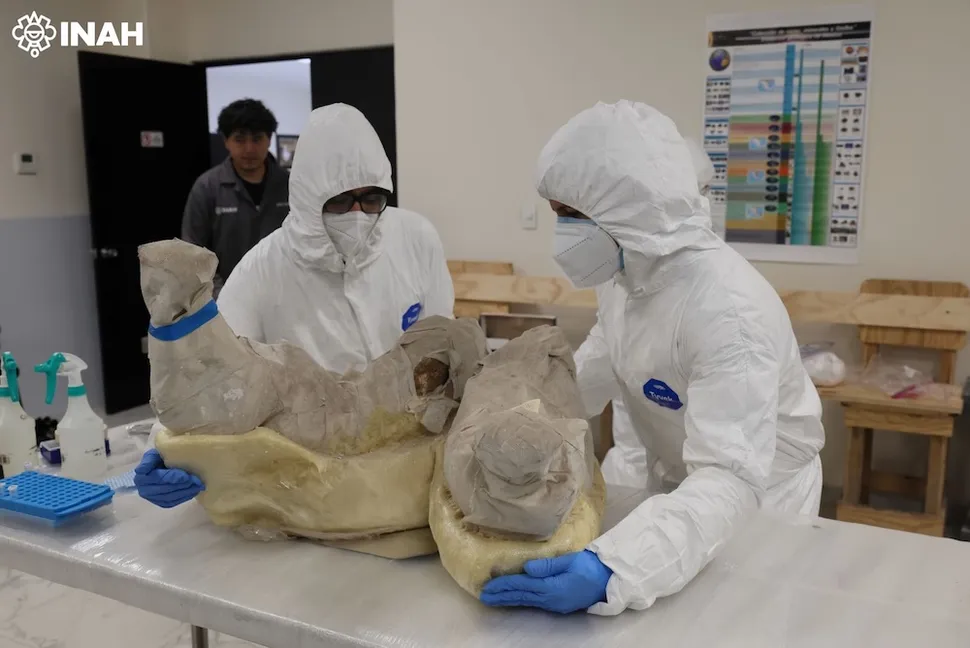

Extracting DNA in hot climates is notoriously difficult — Sánchez-Quinto compared it to “trying to preserve ice cream in the sun.” Yet his team managed to sequence 61 mitochondrial genomes from 83 mammoth teeth, dated between 13,000 and 16,000 years old. The study, published August 28 in Science, marks a breakthrough for paleogenomics in the tropics.

What they found, however, was puzzling. Earlier research shows Columbian mammoths descended from hybrids between Eurasian steppe mammoths and woolly mammoths that crossed the Bering land bridge up to 800,000 years ago. But Mexican Columbian mammoths appear genetically distinct from those in the U.S. and Canada.

“The common ancestor of the Mexican population split earlier,” explained study co-author Eduardo Arrieta-Donato. “You can imagine her as a great-great-grandmother whose descendants migrated south and became isolated — and that isolation shaped their unique DNA.”

That uniqueness isn’t limited to mammoths. Ancient black bears and mastodons from Mexico also show genetic differences compared with their northern relatives. One species might be coincidence; three suggests a broader evolutionary pattern.

“This tells us Columbian mammoth evolution was far more complex than we thought,” Sánchez-Quinto said. “Mexico holds genetic variation not seen elsewhere.”

The study has broader implications too. It challenges the long-held assumption that ancient DNA cannot survive in tropical environments — and demonstrates that cutting-edge paleogenomic work can be done entirely in Latin American labs.

“This is a mammoth achievement,” said Love Dalén, an evolutionary geneticist at Stockholm University not involved in the research. “Recovering DNA from tropical Late Pleistocene fossils is extraordinary.”

The findings open the door to deeper questions: Why did species in Mexico develop such unique genetic lineages? Was it climate, geography, or isolation at work? Answering that will require sampling more fossils across wider regions.

As Sánchez-Quinto put it: “This is more than enough reason to explore biodiversity through time in the tropics — ideally led by local scientists.”