Complete fossils from an enormous shark that lived alongside the dinosaurs reveal crucial information about this enigmatic predator — including it being an ancient relative of the great white shark.

The sharks, from the genus Ptychodus, were first discovered in the mid-eighteenth century. Descriptions of this genus were largely based on their teeth — which could be nearly 22 inches (55 centimeters) long and 18 inches (45 cm) wide, and were adapted for crushing shells — found in numerous marine deposits dating to the Cretaceous period (145 million to 66 million years ago).

Without the ability to examine a fully intact specimen, researchers had hotly debated what the shark’s body shape might look like — until now.

“The discovery of complete Ptychodus specimens is really exciting because it solves one of the most striking enigmas in vertebrate paleontology,” lead author Romain Vullo, a researcher at Géosciences Rennes, told in an email.

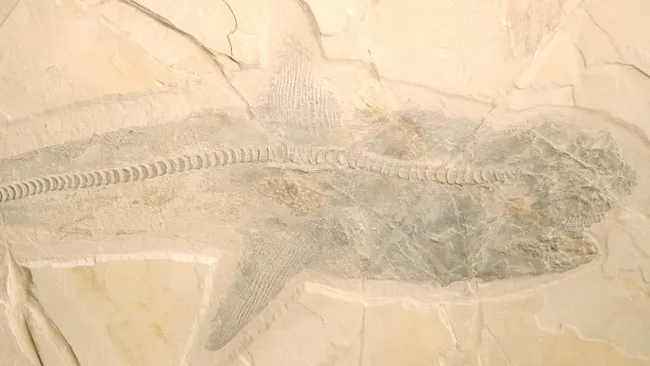

In a study published Wednesday (April 24) in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, researchers have described complete fossils of the shark discovered in limestone quarries in Nuevo León, northeastern Mexico. Its outline was still fully preserved, and its body shape suggests it hunted sea turtles — which could explain its extinction around 76 million years ago as it was competing with other animals that ate the same prey.The specimens “show an exquisite preservation,” because they were deposited in a quiet area with no scavengers, Vullo said. “The carcasses of animals were rapidly buried in a soft lime mud before being entirely disarticulated.”Analysis of the fossils reveals this large predator belonged to the mackerel shark group (Lamniformes), which includes great whites (Carcharodon carcharias), mako, and salmon sharks. It grew to around 33 feet (10 meters) long and is known for its massive, grinding teeth, which are unlike those we see in sharks today.

Long-standing beliefs about Ptychodus’ diet were upended with the discovery of new fossils, challenging the notion that it feasted solely on seabed invertebrates. These findings revealed a sleek body structure, hinting at its role as a swift, open-water predator. “The fossils from Mexico show a Ptychodus resembling the modern porbeagle shark,” Vullo noted, yet with distinct grinding teeth. This revelation prompted researchers to propose a diet consisting of large ammonites and sea turtles.

“Ptychodus carved out a niche in the Late Cretaceous oceans,” Vullo explained, as it was uniquely adapted to prey on hard-shelled creatures like turtles. This specialization may have contributed to its demise roughly 10 million years before the Cretaceous period’s end. “As the Cretaceous drew to a close, these formidable sharks likely faced stiff competition from marine reptiles like mosasaurs, all vying for the same prey,” he added.