Researchers have mapped the distribution of a jellyfish subspecies and found that creatures which lack a distinctive “knob” are somehow prevented from leaving the Arctic.

Invisible Oceanic Divide May Be Trapping Arctic Jellyfish in the North

A puzzling underwater barrier may be preventing certain deep-sea jellyfish in the Arctic from venturing into the Atlantic Ocean, according to a new study.

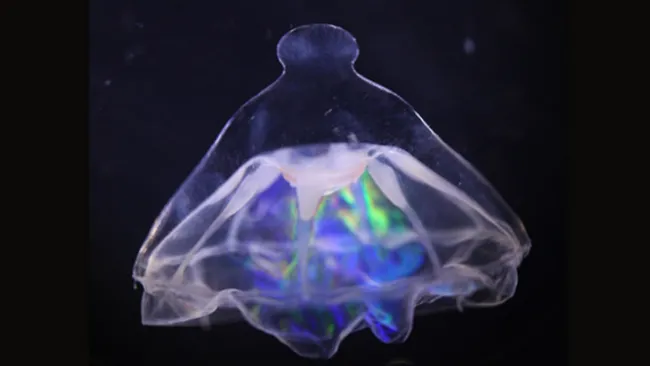

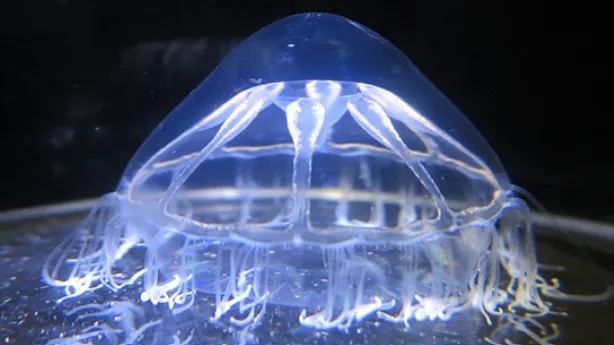

Researchers have been investigating a rare subspecies of jellyfish — Botrynema brucei ellinorae — which typically lives at depths between 1,000 and 2,000 meters (around 3,300 to 6,600 feet). These jellyfish come in two distinct forms: one featuring a small knob on top of their bell-shaped body, and another without it.

“This jellyfish exists in two forms depending on the region — one with a visible knob and one without,” explained lead author Javier Montenegro, a marine biologist at the University of Western Australia. “What’s fascinating is that the knobbed version appears across global oceans, but the knobless form has only been spotted in Arctic and sub-Arctic waters.”

To uncover the reasons behind this curious pattern, Montenegro and his team delved into over a century’s worth of photographic and observational records. By mapping these alongside new genetic analyses, they discovered that despite the differing physical traits, jellyfish from both groups shared striking genetic similarities — particularly with populations in the western Atlantic.

This surprising genetic match revealed that knobless jellyfish in the Arctic closely resemble their knobbed Atlantic counterparts, yet for some reason, they remain confined to the colder northern waters. The culprit appears to be a hidden, non-physical barrier in the deep sea — possibly biological or related to oceanographic conditions.

“The subtle difference in shape, especially around the 47°N latitude, suggests a previously unknown bio-geographic boundary in the Atlantic,” Montenegro noted.

This boundary is thought to lie within the North Atlantic Drift, a warm ocean current extending from the Gulf Stream. Though not a solid wall, it may functionally restrict movement of certain deep-sea creatures. One theory is that jellyfish lacking the knob may be more vulnerable to predators or less suited to survive in the warmer, faster-flowing currents to the south.

Meanwhile, on the Pacific side of the Arctic, the jellyfish face a different kind of blockade. The Bering Strait, at only 50 meters (165 feet) deep, physically prevents deep-sea species like B. brucei ellinorae from traveling southward.

Montenegro believes this discovery has broader implications: “The fact that two morphologically distinct jellyfish forms share a genetic lineage highlights how much we still have to learn about gelatinous marine biodiversity and dispersal,” he said.

The study was published online in Deep Sea Research on July 3 and offers new insights into the invisible boundaries that shape life in the ocean’s depths.