During the last ice age, North America was home to a diverse array of megafauna, including American cheetahs, colossal armadillo-like creatures, and towering giant sloths. However, the mysterious disappearance of these creatures, weighing over 100 pounds (45 kilograms), around 10,000 years ago has long confounded scientists.

While some studies attribute their extinction to rapid warming periods known as interstadials and human hunting during the ice age, others suggest a combination of factors. The debate over the true cause of their demise continues to captivate researchers, driving ongoing exploration and discovery of fossils across the continent.

As the search for answers persists, each new fossil unearthed offers a glimpse into the lives of these magnificent creatures, shedding light on their behaviors and ecology during a pivotal period in Earth’s history. Here’s a unique look at 15 extinct animals from North America’s last ice age, revealing the fascinating stories behind their disappearance.

1. Saber-toothed cat

The saber-toothed cat (Smilodon fatalis) prowled the Earth from approximately 400,000 to 11,000 years ago, as documented by the Natural History Museums of Los Angeles County. This formidable feline boasted an imposing stature, weighing between 350 to 620 pounds (160 to 280 kg) and measuring an average of about 5.75 feet (1.75 meters) from its hindquarters to its snout, excluding its tail, according to insights from the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance. Although similar in size to a modern African lion (Panthera leo), S. fatalis possessed shorter and more robust limbs. However, its most distinguishing feature was its formidable blade-like, serrated canine teeth, or sabers, which reached an impressive length of nearly 7 inches (18 centimeters).

2. Ice age coyote

The University of California Museum of Paleontology houses a composite skeleton of an ice age coyote.

The ice age coyote (Canis latrans orcutti), also referred to as the Pleistocene coyote, surpassed its modern descendants in size and prowess. A study published in the journal PNAS in 2012 revealed that this ancient member of the Canidae family weighed between 33 and 55 pounds (15 to 25 kg), with some individuals rivaling the size of contemporary wolves (Canis lupus). In contrast, today’s coyotes (Canis latrans) typically weigh only around 22 to 40 pounds (10 to 18 kg), as outlined in a statement accompanying the study.

Distinguished by a thicker and deeper skull, as well as more robust teeth designed for carnivorous diets, the Pleistocene coyote exhibited adaptations suited for hunting larger prey and thriving as a formidable carnivore, according to the study’s findings.

3. Ancient bison

The ancient bison (Bison antiquus) roamed North America from approximately 240,000 to 10,000 years ago, as noted by the National Park Service (NPS). Towering at 7.5 feet (2.3 m) in height, stretching 15 feet (4.6 m) in length, and weighing a hefty 3,500 pounds (1,600 kg), it surpassed its modern counterpart, the American bison (Bison bison), by 25%. Additionally, its horns boasted greater length compared to those of contemporary bison. Given their similarities and temporal proximity, these herbivores are believed to be the ancestors of the American bison, according to the NPS.

4. Ancient walrus

In 1980, researchers unearthed the nearly intact remains of Gomphotaria pugnax, an extinct giant pinniped, in Southern California. Dating back approximately 8.5 million to 5 million years ago during the late Miocene epoch, this colossal creature sported a massive 18.5-inch-long (47 cm) skull adorned with prominent upper and lower canine tusks. It is believed that G. pugnax navigated shallow waters, utilizing its tusks to sift through sediment on the seafloor while foraging for sustenance, likely consisting of hard-shelled invertebrates like mollusks.

“In life, G. pugnax was apparently a huge, heavy-bodied pinniped, featuring a prominent high forehead, particularly among males, reminiscent of the California sea lion (Zalophus californianus), and characterized by diminutive eyes,” the researchers noted in their study.

5. Scimitar-toothed cat

The scimitar-toothed cat (Homotherium) boasted formidable weaponry in the form of large canine teeth, powerful forelimbs, and a robust physique, all of which contributed to its prowess as a predator during the Pleistocene era, as revealed in a 2020 study published in the journal Current Biology. While fossils of this ancient feline have been uncovered in Eurasia, it made its mark in North America during the last ice age after traversing the Bering Land Bridge. Remnants of Homotherium have been unearthed at significant sites such as the La Brea Tar Pits in Southern California, as well as in various regions across the United States, including Alaska, Idaho, and Texas.

6. North American horses

When European settlers arrived in the New World, they brought horses with them, unaware that the thunderous echoes of ancient hooves once reverberated across the continent.

North America was once home to ancient horses, which roamed the land from approximately 50 million to 11,000 years ago, marking their extinction at the close of the last ice age, as explained by Ross MacPhee, curator emeritus of mammalogy at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

“The curious aspect of this extinction is that while horses vanished from North America, they continued to thrive in Eurasia and Africa, giving rise to their modern descendants — donkeys, asses, and the horses we know today,” MacPhee shared.

7. Glyptodon

Glyptodon resembled an oversized armadillo, boasting a protective shell composed of bony plates like its smaller relative.

Believed to have migrated from South America to North America through the Isthmus of Panama around 2 million years ago, this armored behemoth thrived in coastal regions of present-day Texas and Florida, according to insights from MacPhee. However, the herbivorous creature met its demise 10,000 years ago, joining the ranks of extinct species.

8. Mastodons

Mastodons (Mammut) ventured into North America around 15 million years ago, traversing the Bering Strait land bridge, preceding their relative, the mammoth, as documented by the Yukon Beringia Interpretive Centre in Canada.

Distinguished by their less intricate teeth, featuring cone-shaped cusps on their molars, mastodons were adept at chewing leaves, twigs, and branches from both deciduous and coniferous trees. They also favored wetland plants lacking abrasive material present in terrestrial plants, as explained by MacPhee. Standing slightly shorter than mammoths, both species ranged in height from 7 to 14 feet (2 to 4 m), boasting shaggy coats for insulation against the cold.

Notably, mastodons boasted lengthy, curved tusks reaching up to 16 feet (4.9 m) long, while mammoths showcased more coiled tusks by comparison.

9. Mammoths

Mammoths (Mammuthus) made their way to North America approximately 1.7 million to 1.2 million years ago, as noted by the San Diego Zoo. Despite some anatomical disparities between mammoths and mastodons, both belong to the proboscidean family. Mammoths boasted fatty humps on their backs, likely serving as reservoirs of nutrients and sources of warmth during cold spells.

Distinguished by their flat, ridged molars, mammoths possessed teeth adapted for slicing through fibrous vegetation, contrasting with the cusped teeth of mastodons, according to MacPhee. Additionally, mammoths share a closer genetic relationship with modern elephants, particularly the Asian elephant, compared to mastodons, as highlighted by MacPhee.

10. Short-faced bear

Here’s the skeleton of a short-faced bear.

Despite its name, this colossal bear didn’t actually possess a short face. However, compared to its elongated arms and legs, it gave off the impression of having one, as noted by MacPhee. He likened it to a grizzly bear on stilts, given that its limbs were at least one-third longer than those of a contemporary grizzly.

“It had exceptionally long forelimbs and hind limbs,” likely aiding it in achieving high speeds, he remarked. While modern bears can muster short bursts of speed, “they’re not built for sustained running,” he added.

Nevertheless, the elongated limbs of the bear remain a puzzle for scientists.

“One theory suggests that short-faced bears pursued their prey akin to cats, but for various reasons, that hypothesis has fallen out of favor,” he explained. “We’re uncertain why they evolved to have lengthy legs.”

Currently, researchers are on the lookout for clues that might shed light on whether the carnivore functioned primarily as a hunter, a scavenger, or both, according to MacPhee.

11. Dire wolf

Dire wolves met their end roughly 13,000 years ago, yet their remains are abundant in California’s La Brea Tar Pits and Wyoming’s Natural Trap Cave. These fossilized skeletons reveal that dire wolves (Canis dirus) were approximately 25% heavier than their modern gray wolf counterparts (Canis lupus), tipping the scales at 130 to 150 pounds (59 to 68 kg), as outlined by the Florida Museum of Natural History.

However, despite their robust build, dire wolves boasted shorter limbs than C. lupus, indicating they weren’t built for speed, the museum noted.

On the canid family tree, dire wolves diverged from wolves around 5.7 million years ago, positioning them as distant relatives of present-day wolves, per a 2021 study in the journal Nature. Unlike other canid species that traversed between Eurasia and North America, dire wolves evolved exclusively in North America, and they refrained from interbreeding with coyotes or gray wolves, the study unveiled.

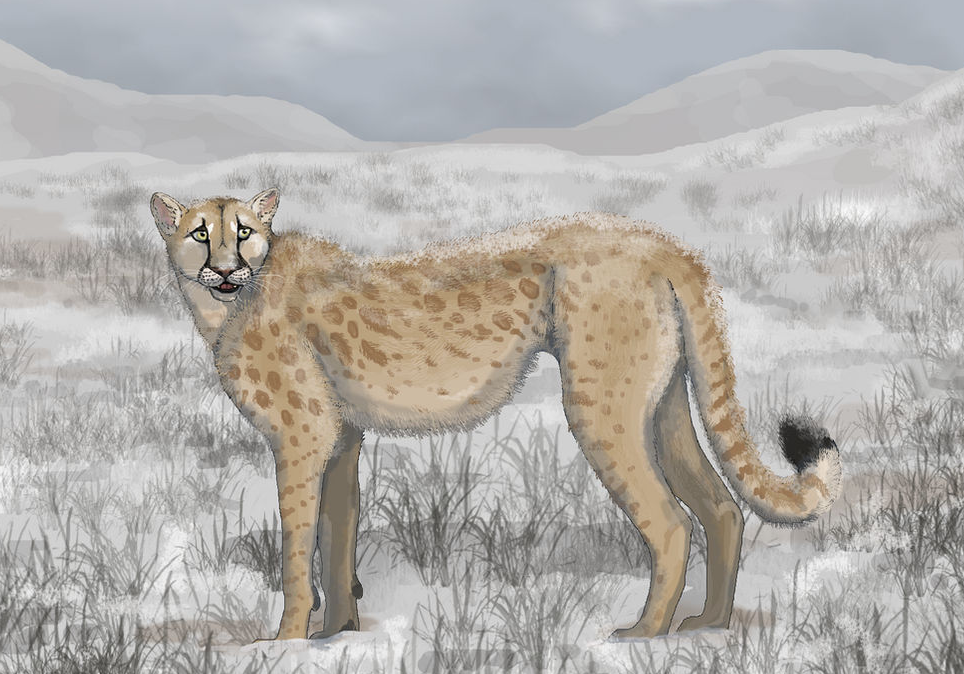

12. American cheetah

The American cheetah stood slightly taller than its modern counterpart, with a shoulder height of approximately 2.75 feet (0.85 m) and a weight of around 156 pounds (70 kg). However, despite its size, the American cheetah likely wasn’t as swift: It possessed slightly shorter legs, indicating it may have been more adept at climbing than running, as per the San Diego Zoo.

Researchers dubbed it Miracinonyx inexpectatus — “mira” meaning “wonderful” in Latin, and “acinonyx” and “onyx” derived from the Greek words for “no movement” (due to the misconception that cheetahs lack retractable claws) and “claw,” respectively, the zoo explained. “Inexpectatus” translates to “unexpected” in Latin, bestowing upon the feline a name that roughly means “wonderful unexpected cheetah with immobile claws.”

The first-known fossil of M. inexpectatus, discovered in present-day Texas, dates back to the Pliocene, approximately 3.2 million to 2.5 million years ago, according to the zoo. They vanished from the Earth about 12,000 years ago.

13. Ground sloth

The ground sloth was significantly larger than its modern counterparts.

When President Thomas Jefferson learned about a peculiar claw fossil discovered in Ohio, he tasked explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark with seeking out giant lions during their western expedition to the Pacific. However, the claw turned out not to belong to a lion but to Megalonyx, an extinct ground sloth, as noted by MacPhee.

Similar to Glyptodon, Megalonyx journeyed to North America from South America. Ground-sloth fossils suggest these creatures began inhabiting South America approximately 35 million years ago, according to the San Diego Zoo.

A Megalonyx fossil dating back 4.8 million years was unearthed in Mexico, with subsequent specimens found in present-day America, particularly in regions once adorned with forests, lakes, and rivers. During warmer interglacial periods, Megalonyx ventured as far north as the Yukon and Alaska, MacPhee explained.

“However, when temperatures dropped, the sloth wasn’t well-suited for the cold, prompting it to migrate southward,” he added.

Standing at about 9.8 feet (3 m) tall and weighing an estimated 2,205 pounds (1,000 kg), Megalonyx jeffersonii persisted until roughly 11,000 years ago, according to the zoo’s records.

14. Giant beaver

The giant beaver (Castoroides) is predominantly known from fossils in the Great Lakes region, which is “perhaps no surprise for a beaver,” MacPhee noted. However, other fossil discoveries indicate that this massive creature once roamed as far south as South Carolina and the American Northeast.

Similar to Megalonyx, the giant beaver migrated into Alaska and the Yukon during interglacial periods but retreated southward when temperatures cooled, MacPhee explained.

Castoroides was exceptionally large for a beaver, weighing up to 125 pounds (57 kg), significantly surpassing the roughly 44-pound (20-kg) North American beaver (Castor canadensis) seen today. Intriguingly, modern beaver remains have been found in the same deposits as those of their ancient counterparts, implying similar lifestyles, MacPhee added.

15. Camels

The skeletal remains of Camelops, also referred to as “yesterday’s camel”.

Camels that once roamed North America are known as Camelops, derived from Latin for “yesterday’s camel.” However, Camelops is more closely related to llamas than to today’s camels, according to the San Diego Zoo.

Camelops and its ancestors were native to the states. Fossils indicate that the camelid family originated in North America during the Eocene period, around 45 million years ago. It inhabited open spaces and arid regions, although it remains uncertain whether it possessed the water-conserving abilities seen in modern camels, MacPhee explained.

Standing approximately 7 feet tall (2.2 m) at the shoulder, Camelops weighed up to 1,764 pounds (800 kg) and featured a short tail.