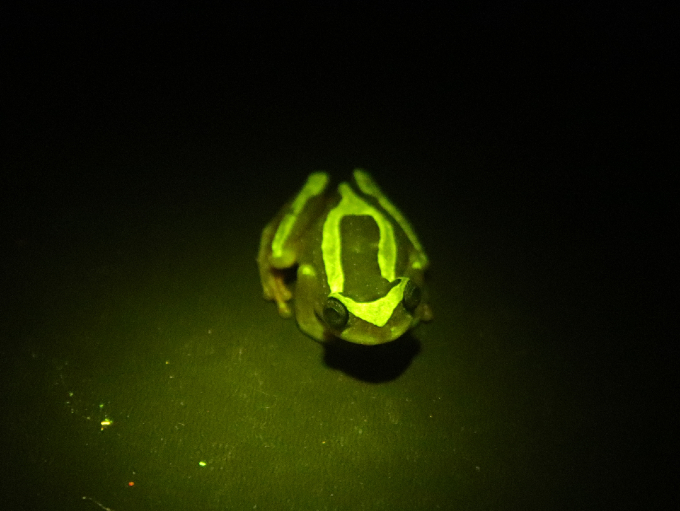

Under twilight conditions, the frogs’ skin may emit visible colors easily discernible by their amphibian counterparts.

In the dim twilight hours, many frogs may be capable of emitting a faint green or orange glow.

A survey of hundreds of frogs in South America shows that far more frogs are biofluorescent than previously thought, researchers report in a preprint posted July 28 at bioRxiv.org. The ghostly colors may have a role in the frogs’ communication with members of the same species, the scientists say.

The findings “are a reminder to check our own perception as humans,” says Jennifer Lamb, a herpetologist at St. Cloud State University in Minnesota who was not involved with the research. “We are very visually dominant in terms of our senses. And other animals are too, but they might be experiencing that visual world differently than we are.”

Biofluorescence occurs in many types of creatures. It happens when an organism absorbs light at one wavelength, or color, and reemits it at a different wavelength with lower energy. Over the past several years, researchers have recognized the trait in a growing diversity of species, from the fur of flying squirrels and platypuses to the nests of certain wasps.

Fluorescence was first discovered in frogs in 2017. Since then, researchers have tested more amphibians for fluorescence, says Courtney Whitcher, an evolutionary biologist at Florida State University in Tallahassee. But investigations of frog biofluorescence have used just one or two light sources she says, usually violet or ultraviolet light.

To get a more detailed and cohesive picture of fluorescence in frogs, Whitcher and her colleagues tested frogs using five different light sources covering a range of wavelengths from green to UV. From March to May 2022, the team captured and shone lights on 528 individual frogs in Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru and measured any reemitted light.

All 151 frog species they tested had some degree of fluorescence, ranging from 2 percent of the original light intensity to well over 90 percent. Prior to this study, less than two dozen of the 42 frog species that had been previously tested were considered fluorescent.

The frogs’ green and orange fluorescence was most intense under blue light that dominates at twilight. This is similar to how many salamander species fluoresce under blue light, Lamb says.

Fluorescence in land living animals “was recently thought to be rare, and when people go out looking for it, surveying across multiple species, it turns out it’s everywhere,” says zoologist Linda Reinhold, recently a graduate student at James Cook University in Queensland, Australia. “It was only because no one had looked before.”

Many of the frogs’ body parts that strongly fluoresced are also involved in signaling to other frogs. Much of the fluorescence seemed centered on the throat and underside of the frogs, which are commonly used in courtship rituals. “While they’re calling, that vocal sac region is expanding and contracting,” Whitcher says. Fluorescence may make for a more noticeable display.

The green glow is probably something other frogs can see, the researchers say. The team found that in the twilight hours — a time when frogs tend to court and mate — frog eyes are quite sensitive to the particular green light that’s emitted from the frogs’ skin. The orange fluorescence, on the other hand, may be intended for a different receiver, such as a predator. It may serve as camouflage or a warning signal, Whitcher says.

It’s “astonishing” how widespread fluorescence is among these frogs, says evolutionary biologist Mark Scherz, of the Natural History of Denmark in Copenhagen. “Not a single one of the species they tested failed to fluoresce,” he says, adding that testing the frogs against a variety of light wavelengths might help explain the fluorescence rate.

But he is skeptical that the fluorescence would be strong enough for communication purposes. Twilight is much dimmer than daylight, he says, so there may not be much light available for conversion to an emerald glow.

Whitcher is now investigating whether fluorescence in male frogs influences female frogs’ mating choices. “Maybe there’s a threshold of fluorescence intensity that is needed in order to elicit some kind of behavioral response,” she says.