A team of Brazilian scientists has solved a decades-old puzzle in paleobotany by reexamining a fossil plant from southern Brazil. Their work led to the creation of a new genus, Franscinella, to house the species now called Franscinella riograndensis. This research, part of Júlia Siqueira Carniere’s master’s thesis (now a doctoral student at Univates), was published in Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology.

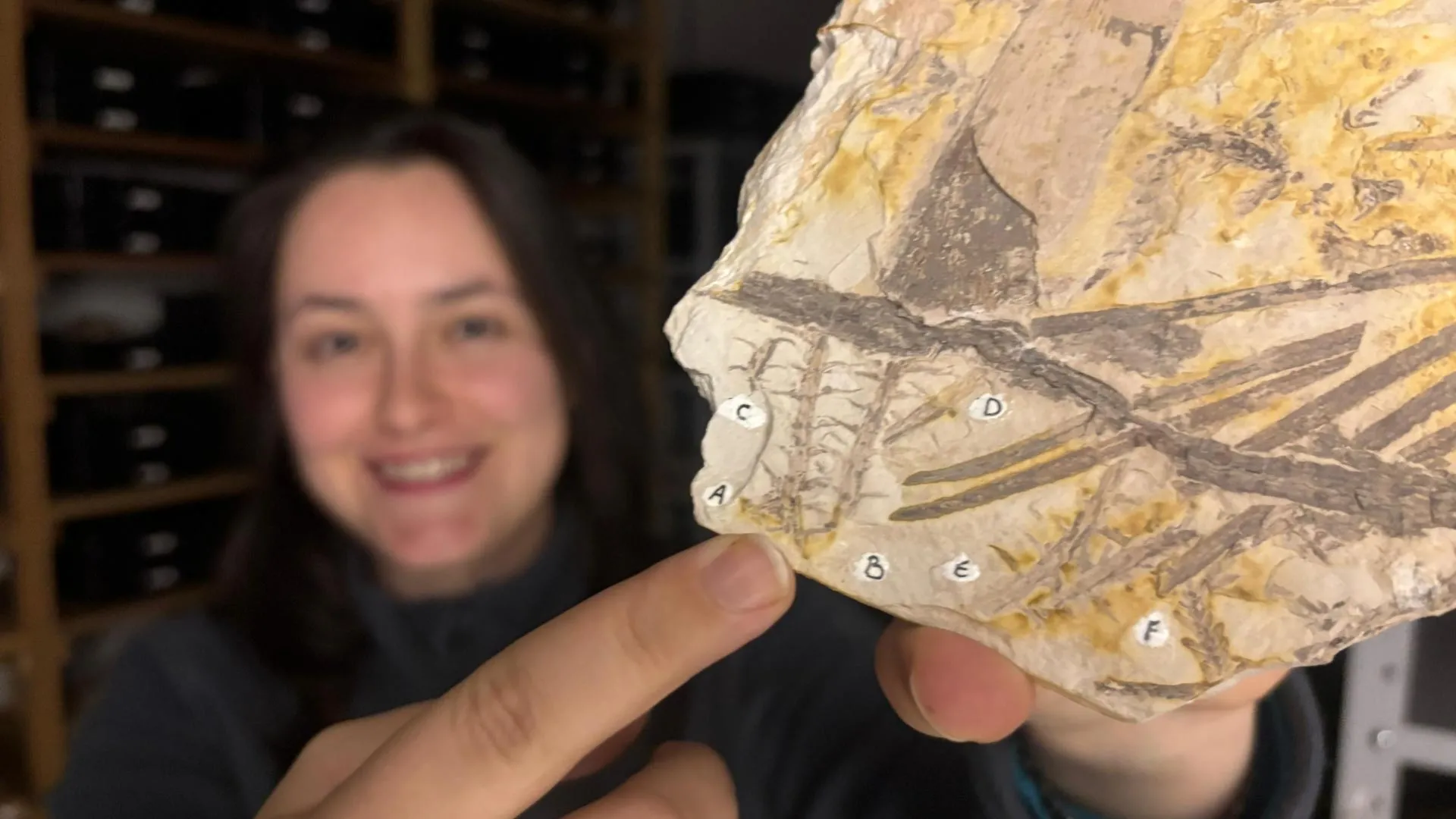

Previously classified as Lycopodites riograndensis, the fossil had been studied only for its general stem morphology. Using modern microscopy techniques, including scanning electron microscopy (SEM), vinyl polysiloxane (VPS) silicone molding, and transmitted light microscopy, researchers uncovered key anatomical features that justified a reclassification. These included isotomic branching of stems, preserved tracheids in the vascular cylinder, and trilete spores with verrucate sculpture preserved in situ.

Finding the spores in situ—still within the plant’s reproductive structures—was especially important. It marks the first record of lycopodites with in situ spores in the Permian strata of Brazil’s Paraná Basin, connecting visible plant structures (macrofossils) with microscopic reproductive evidence (microfossils). The spores correspond to the palynological genus Converrucosisporites, common in Permian deposits, allowing researchers to link fossil plants to their ecosystems and improve interpretations of ancient vegetation.

This discovery provides new insights into the diversity and evolution of vascular plants in Gondwana during the Permian period. Lycosids like Franscinella were historically lumped under broad genera such as Lycopodites due to limited data. By revisiting classic fossils with modern tools, scientists can now reconstruct Permian plant communities with greater accuracy and contribute to biostratigraphy, the dating and correlation of rock layers using fossils.

The project was a collaborative effort involving Univates, itt Oceaneon/Unisinos, the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS), and international institutions like Senckenberg in Germany, supported by Brazilian science agencies including CNPq and CAPES.

This study demonstrates how new technology and interdisciplinary approaches can transform our understanding of ancient life, revealing rare and previously inaccessible information about plant evolution more than 250 million years ago.