From worms with squid-like tentacles to fish with teeth on their tongues, here are some of the most alien-looking creatures in the deep ocean.

The deep sea, a realm beyond 656 feet (200 meters) below the ocean’s surface, is a mysterious world where sunlight fades to complete darkness, temperatures plummet, and pressures become crushing. In this alien environment, life has evolved in bizarre and extraordinary ways, resulting in some truly otherworldly creatures.

In these depths, survival demands remarkable adaptations. Many deep-sea animals have developed bioluminescent organs to lure prey or communicate in the pitch-black surroundings. Others boast enormous mouths, expandable stomachs, or oddly shaped eyes, all tailored to their extreme habitat. These adaptations not only ensure their survival but also contribute to their nightmarish, yet fascinating, appearance.

Thanks to advancements in deep-sea exploration over recent decades, scientists have cataloged an array of these enigmatic residents. Here’s a look at 32 of the most peculiar and intriguing inhabitants of the deep ocean.

Snipe eel

Snipe eels are remarkable deep-sea dwellers known for their beak-like jaws and elongated, slender bodies. They inhabit depths ranging from 980 to 2,000 feet (300 to 600 meters), though some individuals have been recorded as deep as 14,800 feet (4,500 meters).

These eels have notably large eyes relative to their size, an adaptation that helps them spot potential predators in the murky depths. Their uniquely curved jaws remain open while swimming, allowing them to effortlessly snatch passing prey. Snipe eels can reach lengths of up to 6.6 feet (2 meters), depending on the species. Currently, nine distinct species have been identified.

Frilled shark

Named for the distinctive frilled appearance of its gill slits, the frilled shark is a mesmerizing deep-sea predator with an eel-like body that can stretch up to 6.6 feet (2 meters) in length. Its large, flattened head and sinuous swimming style, reminiscent of a snake, set it apart in the ocean’s depths.

Found in deep waters around the globe, the frilled shark moves by undulating its body in a wave-like motion. This ancient shark boasts several rows of needle-sharp, three-pointed teeth, perfectly adapted for tearing into its preferred diet of squid, along with fish and other sharks. Despite its formidable predatory skills, encounters with frilled sharks are rare, leading researchers to believe that this species is dispersed in isolated patches throughout the deep ocean.

Giant sea spider

With legs that can span wider than a dinner plate, giant sea spiders are a striking presence on the ocean floor of both the Arctic and Antarctic. These remarkable arachnids can be found at depths reaching up to 13,100 feet (4,000 meters), where they move slowly in search of food and mates.

Despite their name and appearance, giant sea spiders are not true spiders but share a distant common ancestor with spiders and crabs. They have been evolving independently for hundreds of millions of years, leading to their unique adaptations. Unlike terrestrial spiders, which spin webs, giant sea spiders use a long, tubelike mouthpart to slurp up their prey. Their diet includes anemones, worms, jellies, and sponges.

Remarkably, giant sea spiders house their vital organs, including their breathing apparatus, within their elongated, stilt-like legs, allowing them to thrive in the extreme conditions of the deep ocean.

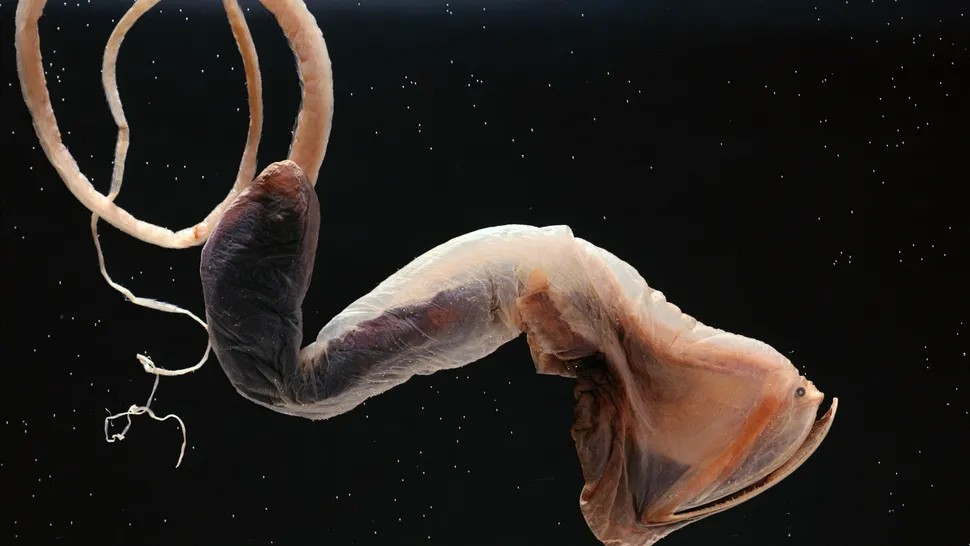

Gulper eel

Known for their striking appearance and formidable feeding strategy, gulper eels—also called pelican eels—are deep-sea dwellers with elongated bodies and enormous mouths that can engulf prey whole. These eels are found across the globe in the twilight zone (660 to 3,300 feet or 200 to 1,000 meters) and the midnight zone (3,300 to 13,100 feet or 1,000 to 4,000 meters), where they navigate the depths of the ocean.

One notable species, the whiptail gulper eel (Saccopharynx lavenbergi), resides at depths between 980 and 6,600 feet (300 to 2,000 meters) in the Eastern Pacific Ocean. Growing up to approximately 3.3 feet (1 meter) long, this eel primarily preys on small fish. It moves by undulating its body, which features a bioluminescent tip. Scientists believe this glowing appendage may function as a lure to attract prey in the dark abyss.

Gulper eels’ unique adaptations, including their immense mouths and bioluminescent lures, make them fascinating examples of deep-sea evolution.

Cookiecutter shark

The cookiecutter shark, named for its distinctive feeding style, is a small, cigar-shaped predator known for carving out circular chunks of flesh from its prey. Growing to between 16.5 and 22 inches (42 to 56 centimeters) in length, this shark uses its serrated bottom teeth to take bites out of animals ranging from fish to larger marine creatures.

Inhabitants of tropical and temperate oceans worldwide, cookiecutter sharks dwell in depths below 3,300 feet (1,000 meters) during the day. At night, they migrate to surface waters to feed, exhibiting a fascinating nocturnal behavior. While these sharks are typically harmless to humans due to their deep-water lifestyle, there have been four reported cases of unprovoked bites off the coast of Hawaii, according to the Florida Museum of Natural History.

Despite their eerie feeding method, cookiecutter sharks are a remarkable example of adaptation in the deep sea.

Dumbo octopus

Named after Disney’s charming elephant, the dumbo octopus is a delightful and enigmatic creature of the deep sea. This genus, which includes 17 species, is part of the broader umbrella octopus family, Opisthoteuthidae. Distinguished by their two ear-like fins extending from above each eye, dumbo octopuses have a unique appearance reminiscent of their namesake.

Residing at the extreme depths of the ocean, dumbo octopuses are the deepest-living octopuses known, with recorded habitats as deep as 13,100 feet (4,000 meters). Remarkably, in 2020, scientists captured footage of a dumbo octopus at an astonishing depth of 22,825 feet (6,957 meters) in the Indian Ocean.

Typically measuring around 8 inches (20 centimeters) in height, dumbo octopuses gracefully swim by flapping their “ears,” which are actually modified fins. They use their webbed arms to glide above the seafloor while foraging for food such as snails and worms. Their gentle, umbrella-like appearance and deep-sea lifestyle make them one of the ocean’s most fascinating and endearing residents.

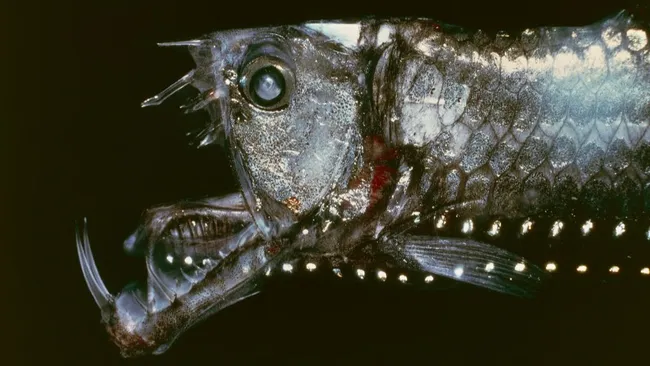

Viperfish

With their menacing needle-like teeth and dramatic adaptations, deep-sea viperfish are among the most intriguing predators of the ocean’s twilight zone. These formidable fish can open their jaws wide enough to ensnare prey and then close them to form a cage-like trap, ensuring nothing escapes their grasp. Notably, some species, such as the Pacific viperfish (Chauliodus macouni), sport two impressive fangs that extend from the lower jaw past their eyes, while others, like Sloane’s viperfish (Chauliodus sloani), possess fangs so large that closing their mouth could potentially puncture their brain.

Viperfish typically reside between 660 and 3,300 feet (200 to 1,000 meters) deep, where they thrive in the dimly lit waters of the twilight zone. Most species grow to about 12 inches (30 centimeters) long. Remarkably, some, including Sloane’s viperfish, have specialized light-producing organs on their bellies. These bioluminescent adaptations help them blend in with the faint light that filters down from above, providing camouflage against predators and aiding in their pursuit of prey.

Goblin shark

The goblin shark, with its otherworldly appearance, resembles something out of a sci-fi movie. Characterized by its distinctive shovel-like snout and an unusual jaw structure, this large shark lurches forward to snatch prey with startling precision. In a remarkable find last year, fishers caught a 15.4-foot-long (4.7 meters) pregnant female off Taiwan, but the maximum size of these enigmatic sharks remains elusive, according to the Florida Museum of Natural History.

Goblin sharks inhabit the deep, mysterious waters along continental slopes and seamounts. The deepest known record of these sharks is from a depth of 4,265 feet (1,300 meters). Their hunting strategy involves detecting changes in electric fields to locate prey such as squid and crustaceans. Once they are within striking distance, their jaws extend outward rapidly to engulf their prey in a swift, gobbling motion.

Siphonophores

Siphonophores are one of the ocean’s most intriguing phenomena, operating as colonial organisms with a remarkable collective efficiency. Each siphonophore is a colony of genetically identical polyps, or zooids, that function together as a single entity. These specialized zooids take on different roles essential for the colony’s survival, including capturing prey, digesting food, and reproduction.

These fascinating creatures can reach extraordinary lengths, with the largest known colony stretching an impressive 154 feet (47 meters) long and 49 feet (15 meters) in diameter. However, most siphonophores are slender, typically not thicker than a broomstick.

Over 175 species of siphonophores have been identified, many of which exhibit mesmerizing bioluminescence. For instance, the giant siphonophore (Praya dubia) is renowned for its bioluminescent glow, turning a vivid blue when it comes into contact with objects or animals. This species inhabits depths ranging from 2,300 to 3,300 feet (700 to 1,000 meters), where it uses its radiant light to lure prey.

Greenland shark

The Greenland shark stands as one of the ocean’s most remarkable residents, distinguished not only by its impressive size but also by its extraordinary longevity. This ancient predator roams the icy depths of the North Atlantic and Arctic oceans, diving as deep as 4,000 feet (1,200 meters). Remarkably, Greenland sharks are believed to live for at least 250 years, with some estimates suggesting they may exceed 500 years, making them the longest-lived vertebrates known to science.

Growing up to 24 feet (7.3 meters) in length, Greenland sharks move slowly through the water, likely relying on ambush tactics or scavenging for carrion to sustain themselves. In northern regions, they are hunted for their meat and skin, which can be used to produce leather. Although the flesh is toxic when raw, it becomes safe to eat once properly dried.

With their ancient lineage and remarkable adaptations, Greenland sharks continue to fascinate scientists and enthusiasts alike.

Sea pig

Sea pigs, named for their pink, plump appearance, are intriguing deep-sea dwellers that resemble a charming blend of pig and sea cucumber. These sea cucumbers are equipped with stilt-like tube feet on their undersides, which they use to shuffle through muddy sediments in their quest for food. Their diet consists of algae, dead organisms, and other detritus that settles on the ocean floor.

Reaching lengths of 1.5 to 6 inches (4 to 15 centimeters), sea pigs can inhabit depths as great as 22,000 feet (6,700 meters), making them true residents of the abyss. According to the Monterey Bay Aquarium, these rosy sea cucumbers sometimes gather in vast numbers to feast on the remains of large animals, such as whales, that have sunk to the seafloor.

Their unusual appearance and behavior make sea pigs one of the more fascinating and endearing creatures of the deep ocean.

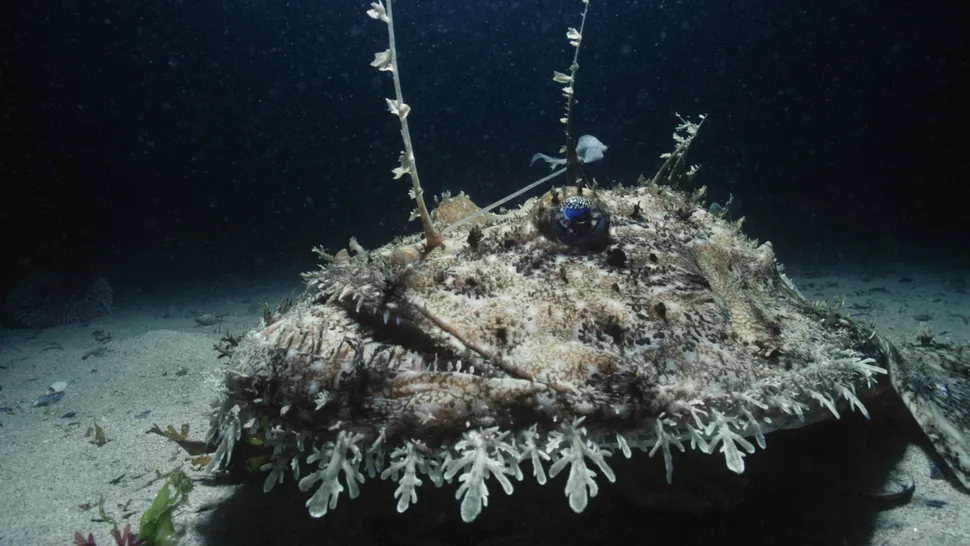

Goosefish

Goosefish, also known as anglerfish, are among the deep ocean’s most peculiar predators. With their flattened heads, flabby bodies, and gaping mouths, these fish are perfectly adapted to their dark, sandy or muddy habitats found more than 3,000 feet (910 meters) deep. Their speckled patterns provide excellent camouflage against the ocean floor, helping them blend seamlessly into their surroundings.

These fascinating creatures use a bioluminescent lure, which dangles from the top of their heads, to attract prey. This glowing bait lures in unsuspecting fish, crustaceans, and sea stars. Once their target is within reach, goosefish strike swiftly with their sharp teeth to capture their meal.

Remarkably, goosefish can “walk” along the seafloor by using their modified pectoral and ventral fins, which function like feet due to their unique joint structure. Additionally, they have a notable reproductive trait: the presence of “accessory” males that provide a constant supply of sperm to females, ensuring successful mating.

Goosefish’s unusual adaptations and behaviors make them one of the most intriguing and enigmatic residents of the deep ocean.

Brier shark

The Brier shark, also known as the birdbeak dogfish, is a deep-sea dweller with a distinctive appearance and a broad range across the ocean. Preferring the cold, dark depths, Brier sharks are typically found between 2,000 and 3,300 feet (600 to 1,000 meters) deep. They are distributed off Australia’s southern coast, throughout the eastern and western Pacific, and in the eastern Atlantic Ocean.

With a long, pointed nose and a grayish-brown body, Brier sharks can grow up to 3.9 feet (1.2 meters) in length. They are known for their potential longevity, reaching up to 35 years of age. Despite their elusive nature, Brier sharks are often caught unintentionally as bycatch, though some fisheries do target them for their flesh and liver oil.

The Brier shark’s unique features and deep-sea habitat make it an intriguing species for marine biologists and ocean enthusiasts alike.

Bigfin squid

The enigmatic bigfin squid, a member of the rarely seen Magnapinna genus, is a marvel of the deep ocean. These elusive cephalopods can grow up to 20 feet (6 meters) long, largely due to their remarkably long arms and tentacles, which can extend up to 20 times the length of their mantle. This distinctive feature, along with their large, protruding fins, gives them an otherworldly appearance.

Bigfin squid are known for their ability to inhabit the deepest parts of the ocean, descending to depths greater than 20,000 feet (6,000 meters). Their long, trailing appendages are covered in microscopic suckers, which are believed to help them capture prey as they drift through the dark depths of the abyss.

Despite their impressive size and unique adaptations, only a handful of sightings have been recorded, and three species have been identified so far. The bigfin squid remains one of the deep ocean’s most mysterious and intriguing residents, captivating scientists with its elusive nature and bizarre features.

Black seadevil anglerfish

The black seadevil anglerfish is a master of the deep sea’s dark and mysterious depths. Sporting a bioluminescent lure that extends like a pole from the top of its head, this fish uses its glowing appendage to attract prey in the pitch-black waters it calls home, from 330 to 15,000 feet (100 to 4,500 meters) below the surface.

Females of the species are notably larger, reaching up to 8 inches (20 cm) in length, while their male counterparts are significantly smaller, measuring just around 1 inch (3 cm). The males lead a parasitic lifestyle, acting solely as sperm-producing accessories. Upon finding a female, a male will attach himself to her, merging his body with hers. Over time, he becomes an integrated part of her, drawing sustenance from her blood while continuously providing sperm for reproduction.

The black seadevil anglerfish exemplifies one of nature’s more extraordinary survival strategies, making it a fascinating subject of study in the realms of deep-sea biology and adaptation.

Purpleback flying squid

The purpleback flying squid is a dynamic and widely dispersed cephalopod that thrives in the warm, tropical, and subtropical waters of the Indian and Pacific Oceans, reaching depths of up to 3,300 feet (1,000 meters). Renowned for their vibrant, iridescent hues, these squids exhibit a range of sizes from dwarf to giant.

One of their most remarkable traits is their speed; purpleback flying squids are adept swimmers, capable of reaching impressive velocities of up to 22 mph (35 km/h). This agility makes them formidable hunters and swift escape artists in their underwater domain.

In fisheries across Japan and Taiwan, purpleback flying squid are sought after both as bait for tuna and for human consumption. However, their meat is often noted for its relatively poor quality, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature. Despite this, their fascinating adaptations and impressive speed continue to capture the interest of marine biologists and seafood enthusiasts alike.

Giant isopod

The giant isopod, a colossal relative of the woodlouse, reigns supreme among isopods as the largest of its kind. Found at depths reaching 7,000 feet (2,100 meters) in the Indo-West Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, this impressive invertebrate measures up to 16 inches (40 centimeters) from head to tail.

With its segmented body, two pairs of antennae, and compound eyes, the giant isopod exemplifies the adaptability of deep-sea life. It roams the ocean floor in search of fallen prey, such as fish carcasses, and utilizes its fan-like tail to execute short bursts of swimming.

The giant isopod is a striking example of deep-sea gigantism—a phenomenon where creatures in the ocean’s depths grow significantly larger than their shallow-water counterparts. This evolutionary pattern may be driven by the reduced predator presence in the abyss or the increased need to transport more oxygen at great depths, according to the Natural History Museum in the U.K. Despite its daunting size, the giant isopod’s life is a testament to the unique adaptations that allow survival in the most challenging environments on Earth.

Bloody-belly comb jelly

The bloody-belly comb jelly, a dazzling inhabitant of the deep, lives at depths ranging from 820 to 4,900 feet (250 to 1,500 meters). Named for its striking crimson stomach, this comb jelly employs its vivid red hue as a clever camouflage in the pitch-black depths of its environment.

The deep-sea darkness causes red light to be absorbed and appear black, making the bloody-belly nearly invisible to potential predators. This adaptation is particularly effective as it conceals the jelly’s stomach, which may contain glowing prey. The jelly’s belly’s red coloration masks any bioluminescence from its recent meals, enhancing its stealth.

Adding to its ethereal allure, the bloody-belly comb jelly features sparkling displays of light, which result from light bouncing off its tiny, hair-like filaments. These filaments, known as cilia, aid in propulsion and create a mesmerizing spectacle as the jelly drifts through the water.

Black swallower

The black swallower is a mysterious denizen of the deep, dwelling at depths ranging from 2,300 to 10,000 feet (700 to 3,000 meters) in temperate and tropical Atlantic waters, including the Gulf of Mexico. This elusive fish, which grows up to 10 inches (25 centimeters) long, is distinguished by its dark, scaleless body and a remarkably large mouth.

Its most striking feature is its expandable stomach, which allows it to consume prey up to four times its own length and ten times its weight. Equipped with hooked, inward-pointing teeth, the black swallower can open its jaws wide to capture sizable prey, then retract the teeth to form a trap, ensuring that the meal is secured and unable to escape.

Rarely seen by humans, black swallowers are primarily encountered when dead specimens float to the ocean surface. Despite their elusive nature, their extraordinary feeding adaptations and the eerie depths they inhabit make them a fascinating subject of deep-sea research.

Vampire squid

Despite its ominous name, the vampire squid is neither a true squid nor a bloodthirsty predator. Its scientific name, which translates to “vampire squid from hell,” hints at its mysterious and somewhat eerie nature, but it is actually one of the two known members of the cephalopod subgroup Vampyromorphida.

Residing in the depths of temperate and tropical oceans beyond 660 feet (200 meters), the vampire squid leads a rather passive existence compared to its more aggressive relatives. It does not hunt or ambush prey; instead, it sustains itself on marine snow—tiny bits of organic debris drifting through the water.

Measuring about 12 inches (30 centimeters) in body length, not including its long arms, the vampire squid boasts the largest eyes proportionate to its body size of any known animal. These remarkable eyes are adapted to its dark, deep-sea habitat. When threatened, the vampire squid performs an impressive display by inverting its eight webbed arms, creating a cloak-like appearance that conceals its body and wards off potential threats.

Though its appearance and name might suggest a fearsome nature, the vampire squid is a gentle, enigmatic creature of the deep sea, perfectly adapted to its dim, distant environment.

Lanternfish

Lanternfish, part of the Myctophidae family, include over 245 species renowned for their distinctive blue-green light organs embedded in their bodies. These light organs are essential for their survival in the dark depths of the ocean. By emitting light, lanternfish can see in the murky underwater environment and communicate with one another. The light also serves a critical function in camouflaging them against predators. By aligning their light organs along their bellies, lanternfish can blend seamlessly with the faint light filtering down from above, thus avoiding casting a shadow that could make them an easy target for predators.

Lanternfish vary in size from 0.8 to 12 inches (2 to 30 cm) in length. They are known for their impressive vertical migrations, traveling up to the surface waters to feed at night before returning to the deeper zones during the day. This behavior not only helps them access a rich source of food but also contributes to their success in deep-sea ecosystems. Lanternfish are incredibly abundant, making up about 60% of all deep-sea fish, and play a crucial role in the marine food web.

Their unique adaptations and substantial presence underscore the lanternfish’s importance in the ocean’s twilight zone, highlighting their remarkable ability to thrive in one of Earth’s most challenging environments.

Hoff crab

The Hoff crab, scientifically known as Kiwa tyleri, is a species of deep-sea squat lobster that resides near hydrothermal vents in the icy waters of the Southern Ocean. It belongs to a group of squat lobsters known as yeti crabs, named for their distinctive white coloration and the hairy setae covering their bodies. The Hoff crab is particularly notable for its densely furry chest, which gives it a unique appearance within this group.

The primary adaptation of Hoff crabs is their ability to harvest bacteria from the hot, mineral-rich fluids emitted by the hydrothermal vents. They use their setae to capture and cultivate these bacteria, which they then consume as their main source of nutrition. This symbiotic relationship with bacteria is crucial for their survival in the extreme conditions of the deep sea.

In their harsh habitat, Hoff crabs can be found in dense aggregations, with surveys indicating that up to 700 individuals may crowd into an area as small as 10 square feet (1 square meter). Despite the challenging environment, including high pressure and extreme temperatures, these crabs thrive and exhibit fascinating behaviors adapted to their unique ecological niche.

Adult Hoff crabs typically grow to about 6 inches (15 cm) in length. Their specialized feeding mechanisms and social behavior highlight their remarkable adaptation to one of the most extreme environments on Earth.

Sea angel

Sea angels are a group of small, gelatinous swimming snails found in cold and temperate waters around the world, down to depths of 2,000 feet (610 meters). Despite their common name, sea angels are not actually angels but are part of the class Gastropoda, which includes snails and slugs.

These fascinating creatures have soft, translucent bodies that range from 1.5 to 3 inches (4 to 8 cm) in length, depending on the species. Sea angels lack shells, a notable difference from their close relatives, the sea butterflies (Thecosomata). Instead of shells, sea angels have two wing-like appendages known as parapodia, which they use to glide through the water. By flapping these parapodia, sea angels are able to propel themselves gracefully through their oceanic habitat.

Sea angels are ambush predators, primarily feeding on sea butterflies, which are smaller, shelled relatives. They use specialized structures called buccal cones to extract their prey from its shell. The buccal cones are adapted to grasp and remove the sea butterflies, making sea angels effective predators despite their delicate appearance.

Their translucent skin allows for a clear view of their internal organs, which can exhibit a pink or orange hue. This transparency not only adds to their ethereal appearance but also helps them blend into the dimly lit waters where they reside.

Sea angels are intriguing examples of the diverse and specialized adaptations found in marine life, demonstrating unique evolutionary paths among oceanic creatures.

Dragonfish

Dragonfish (Stomiidae) are extraordinary inhabitants of the ocean’s deep, residing in the twilight and midnight zones down to depths of 14,800 feet (4,500 meters). While females can grow up to 20 inches (50 cm), males are significantly smaller, ranging from 2 to 6 inches (5 to 15 cm), depending on the species. Notably, females boast impressive fangs — long, translucent teeth embedded with nanocrystals, giving them a bite force stronger than that of many sharks. They also feature a glowing barbel hanging from their chin, which lures in prey. Both sexes of dragonfish are adorned with bioluminescent organs known as photophores, used for communication and attracting prey in the dark abyss.

Cockeyed squid

As implied by its name, the cockeyed squid (Histioteuthis heteropsis) is notable for its asymmetrical eyes. Born with eyes of equal size, the left eye dramatically outgrows the right as the squid matures, eventually becoming more than twice the size and taking on a semi-tubular shape with a yellow lens.

The cockeyed squid adopts a tilted swimming posture, positioning its larger eye upwards to detect the faint down-welling light. This adaptation aids in spotting prey that use light to blend into their surroundings. Meanwhile, the smaller, downward-facing eye offers a broad field of view, enhancing the squid’s ability to detect bioluminescent creatures in the deep ocean.

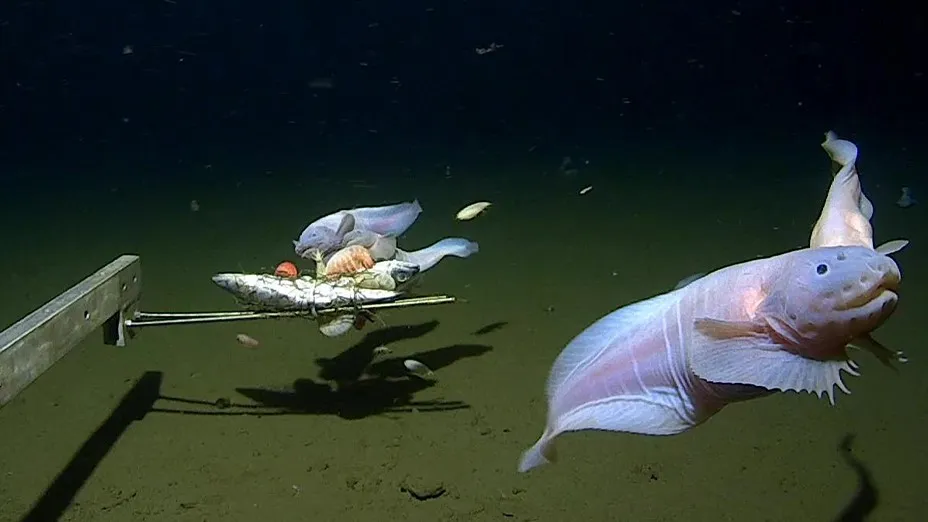

Snailfish

Snailfish are a family of uniquely shaped fish, characterized by their tadpole-like bodies and an average length of around 12 inches (30 cm). Predominantly found in cold waters, some species inhabit the frigid Arctic and Antarctic regions. Notably, a snailfish from the genus Pseudoliparis (species yet to be identified) holds the record for the deepest-dwelling fish, having been captured on film at a staggering depth of 27,349 feet (8,336 m) in the Izu-Ogasawara Trench off Japan in 2023. This surpasses the previous record, also held by a snailfish, observed in the Mariana Trench further south in the Pacific.

The snailfish’s survival at such extreme depths is due to its gelatinous body, which compensates for the lack of a swim bladder—a buoyancy control organ present in many other fish. Additionally, the snailfish’s body is filled with a special fluid known as osmolyte, which shields its tissues from the immense pressure found in the deep ocean.

Pink see-through fantasia

The pink see-through fantasia (Enypniastes eximia), commonly known as the headless chicken monster, is a striking species of sea cucumber notable for its bulbous, translucent body and distinctive ridged fins. Its reddish-purple coloration combined with near-complete transparency makes its internal organs visible. Unlike most sea cucumbers, this species has the unique ability to float vertically in the water column, propelled by an umbrella-like brim that allows it to move with a rowing motion.

Reaching up to 9 inches (23 cm) in length, the pink see-through fantasia is larger than many of its seafloor-dwelling relatives. While it can swim, it primarily spends its time walking along the ocean floor, where it sifts through sediment to find food. Observations indicate that, before swimming away, this sea cucumber may expel waste to lighten its load. E. eximia is found across a wide range, inhabiting depths from 1,640 to 23,000 feet (500 to 7,000 m) globally.

Rabbit fish

The rabbit fish (Chimaera monstrosa), also known as the rat fish, is a unique species related to sharks and rays, found in the northeastern Atlantic Ocean and the western Mediterranean Sea. Characterized by its sluggish swimming style, the rabbit fish relies mainly on its pectoral fins for movement, and it uses its long, tapering tail minimally. This species inhabits depths of up to 5,300 feet (1,660 m).

Rabbit fish have a distinctive defense mechanism: they can raise a venomous spine located on the back of their head, which can deliver a painful sting to predators. Adult rabbit fish can grow up to 5 feet (1.5 m) in length, with their tail accounting for as much as 60% of their total length. Their diet primarily consists of crustaceans and mollusks, which they crush using their fused teeth, evolved into hard plates suitable for breaking down their prey.

Squidworm

The squidworm (Teuthidodrilus samae) is a remarkable marine worm notable for its unique appearance and feeding adaptations. Eyeless and roughly the size of a human palm, the squidworm is distinguished by its 10 long, tentacle-like appendages that extend from its head, each longer than its body. These appendages are used to wave and capture “marine snow,” or particles of organic debris falling from the upper waters.

The squidworm also has 25 pairs of translucent, white paddles along its body, which it uses for swimming. This species was first discovered in 2007 at a depth of 9,500 feet (2,900 m) in the Celebes Sea, situated between Indonesia and the Philippines. Despite its deep-sea habitat, the squidworm is not known to produce bioluminescence, unlike many other deep-sea dwellers.

Deep-sea lizardfish

The deep-sea lizardfish (Bathysaurus ferox) stands as the deepest-dwelling superpredator known, preying on a wide range of creatures, including its own kind, according to NOAA. Equipped with razor-sharp fangs embedded in its jaws and even in its tongue, this fish excels at ambushing prey. It lies in wait on the ocean floor, with its head slightly raised, ready to snatch anything that swims overhead.

This fearsome predator inhabits depths between 2,000 and 11,500 feet (600 to 3,500 m) and grows up to about 25 inches (64 cm) long. Its sensitive eyes are adapted to detect bioluminescence, allowing it to spot prey in the dark depths. Additionally, the deep-sea lizardfish is hermaphroditic, possessing both male and female reproductive organs. This unique trait enables it to mate with any other individual it encounters, a useful adaptation in the sparse and scattered populations of its kind across the world’s oceans.

Deep-red jellyfish

The deep-red jellyfish (Crossota norvegica) is a striking species found in the Arctic Ocean at depths greater than 3,300 feet (1,000 m). Its vivid red body is rounded and measures less than 1 inch (2.5 cm) across, making it a notable presence in the deep sea.

Much about this jellyfish remains a mystery, including its diet. Like other jellyfish, it likely uses its numerous spaghetti-like tentacles to capture prey. The reproductive characteristics of Crossota norvegica are not well understood, and it is unclear whether it requires both male and female individuals for reproduction or if it can reproduce on its own.

Barreleye fish

The barreleye fish (Macropinna microstoma) inhabits the Bering Sea and North Pacific Ocean at depths between 2,000 and 2,600 feet (600 to 800 m). It features a transparent forehead and unique tubular eyes that can rotate, allowing it to look upward to spot potential prey or predators. The eyes contain a yellow pigment that aids in distinguishing bioluminescence from sunlight filtering through the water. Barreleye fish remain stationary in the dark and quickly dart upward to capture prey that passes above, adjusting their eyes to focus forward once the prey is secured.